This article is more than 1 year old

Global spy system ECHELON confirmed at last – by leaked Snowden files

Origins of automated surveillance

Alan Turing, Britain's assistant spy chief, and my mother

I first heard of secret intelligence as a boy. My mother Mary, a mathematician, often reminisced about her wartime work in a top-secret establishment, including two years working alongside a man they called "the Prof." She portrayed an awkward, gangly fellow with a stutter who loved long-distance running and mushrooms he foraged from local woods that no one would touch – and who was a mathematical genius "out of her league.”

"The Prof" was Alan Turing, the wartime breaker of the German Enigma code, inventor of the modern computer, and hero of the recent Oscar-winning film, The Imitation Game.

Almost four decades passed before she found out who it was that she and the Prof had been working for. She had kept a war souvenir, a flirtatious poem given to her by a British general who visited her radio listening station. The poem inspired her army boss to joke that the general intended to propose. When official war records were finally released, we discovered that the general had actually been the assistant chief of Britain's Secret Intelligence Service.

I first stumbled across GCHQ's surveillance network while at school. On a bike outing in Scotland with another science student, we spotted a large hilltop radio station. We pedaled up to find fences, locked gates, and a meaningless sign hung on the wire that read: "CSOS Hawklaw.” Nearby, we found a ubiquitous British chippie – a fish-and-chip shop – and asked the proprietor, “What do they do there?”

“They never talk,” we were told. “It's a secret government place.”

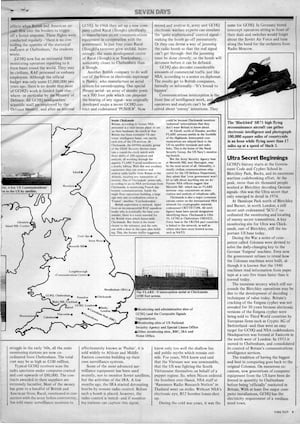

Bombshell exclusive ... The Eavesdroppers article by Duncan Campbell in 1976.

Click here for the full PDF

At the public library, I checked every phone book in the country, looking for more sites with the same name. The initials stood for "Composite Signals Organisation Station" – hardly revealing. Among the sites I found was GCHQ's Bude station in Cornwall, England, now exposed as a global epicenter of NSA-GCHQ internet cable surveillance. Back then, it was called “CSOS Morwenstow.” Four years and a degree in physics later, I found a press report that CSOS was part of GCHQ.

Armed with these leads, in May 1976, I wrote The Eavesdroppers, the first-ever story about GCHQ, alongside American journalist Mark Hosenball, for London's then-radical entertainment magazine Time Out.

I was later told by high-level government contacts that I had been under surveillance while reporting The Eavesdroppers. The "watchers," from MI5, were first rate. I never spotted anything. But while following me and tapping my phone, British security learned an uncomfortable truth: all of the sources for my secret information were Americans, whose free speech was not controlled by British laws.

The Eavesdroppers put GCHQ in view as Britain's largest spy network organization. "With the huge US National Security Agency as partner, [GCHQ] intercepts and decodes communications throughout the world,” I wrote.

The very existence of GCHQ and the SIGINT network were then closely guarded secrets. My article was based on open sources and help from ex-NSA whistleblowers. One was Perry Fellwock, a former US Air Force analyst who helped expose the scale of illegal NSA surveillance during Watergate.

Deported

My co-author Mark Hosenball, a US citizen (now an investigative reporter for Reuters), was quickly slated for deportation as a threat to national security. He faced a security inquiry and then expulsion, knowing only that he was accused of having “sought information for publication which would be harmful for state security.” The ban was lifted more than 20 years ago.

One part of our article that caused concern was a centerpiece map (compiled from phone books) showing NSA and GCHQ monitoring stations scattered across Britain. One of the locations I identified, Menwith Hill Station, a tapping center in the heart of England, has now been revealed in Edward Snowden's papers to be a global center for planned cyberwar.

We also reported that electronic versions of the Enigma cypher were being sold to developing countries by European firms such as Crypto AG of Switzerland before those nations knew Britain had cracked the code.

The day after publication, GCHQ relayed my article around the world. At one major overseas center, I was later told that the local station chief came into a morning meeting, incoherent with rage and "frothing at the mouth,” according to a security official present. Unable to explain in grammatical sentences what had upset him, the chief pulled out and hurled down a telegraphed copy of my article.

After Hosenball was ordered to leave Britain in 1977 for his part in writing the piece, new whistleblowers came forward. One was John Berry, who had worked for GCHQ in Cyprus. Berry revealed in a letter to Britain's National Council for Civil Liberties that:

GCHQ ... monitors the radio networks of so-called friendly countries and even the commercial signals of UK companies. The extent of intelligence activities ... and the resources which the British Government deploys in this area are largely unknown. The apparatus could transform Britain into a police state overnight.

That is what led us to Berry’s flat that unforgettable February evening.