This article is more than 1 year old

Comet lander drill cliffhanger as last dregs of power used

Will humanity find out its origins in space ... or not? Tune in at midnight

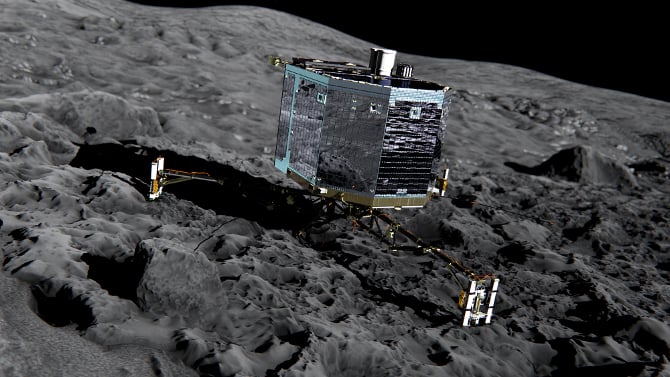

The Philae team has opted to use what could be the last of the comet-catching lander’s power to deploy its drill, in the hopes of collecting the chemical analysis that could answer fundamental questions about life on Earth.

In a nail-biting cliffhanger end to the lander's story, the plucky probot’s protuberance had descended 25cm from the lander’s baseplate before its mothership Rosetta slipped behind Comet 67P’s horizon and out of radio reach earlier today (Friday afternoon UK time). That leaves all the ESA and DLR boffins at the edge of their seats, waiting to see if the fridge-sized probe will have enough juice left to be contactable in the next window late tonight (UK time).

“We have activated the drill, we started to drill, but then we lost contact again,” project manager Stephan Ulemac said. “So the drill has been active already today, but whether it will actually take samples and we succeed in bringing those samples in and putting them in COSAC, we’ll find out this evening.”

Unfortunately, one of the last commands the team at the European Space Agency and Germany’s space agency DLR sent up to Philae relayed via the Rosetta mothercraft didn’t make it through – and it was the one to tell the craft to go into low-power mode instead of standby, which would have saved two watts.

It doesn’t sound like much, but every tiny bit helps at this stage, as Valentina Lommatsch of the DLR Lander Control Centre’s mission team explained.

“Last night, we had calculated that we needed 80 watt-hours to complete the block we’re on just now and we thought that we might have around 100 left,” she said. “So it’s going to be really, really close.”

The team still isn’t sure exactly where the lander ended up after bouncing twice on its historic touchdown, but they now believe that all three feet are on the ground. The reason Philae isn’t getting any energy to recharge its batteries is because it has fetched up in the shadow of a rock formation.

“From the solar panels, what we have is about 1.5 hours of less than one watt on one panel and within that time we also have twenty minutes of about 3 to 4 watts. The lander needs 5.1 watts to boot so we have to at least get that. And then in order to charge the battery, we have to heat it up to 0 degrees Celsius, which would mean that we would need 50 to 60 watt hours a day and still have some daylight left to charge the battery,” Lommatsch said.

“I can confirm from the solar data that we have not moved at all from the first panorama shot, we were just unlucky to land in a corner.”

The fact that the lander ended up in shade is disappointing, but it’s already had more than its fair share of luck. Despite the fact that its harpoons failed to fire on descent, anchoring it to its space-rock target, the lander still made its touchdown, albeit a bouncy one that’s left Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera team scrambling to try to locate it.

“We’ve been trying to shift and rearrange things to try to locate the lander,” said Rosetta project scientist Matt Taylor. “We’re trying our best to give the OSIRIS team the data they need to find the lander. We’re on the cutting edge of science, we don’t have results yet, but hang in there… it’s going to be wonderful!”

The science teams already have around 80 per cent of the data they were hoping to collect from the history-making comet landing and they still have Rosetta, a comet-orbiting satellite that’s working perfectly and continues to collect its own science observations.

“Maybe the battery will be empty before we get contact again, but we shouldn’t be too disappointed after all this success,” Ulemac said philosophically.

If they do manage to regain contact though, they’re planning to go for broke. The first step will be the drill, doing their best to make sure it’s successfully taken a sample and delivered that sample to Philae's COSAC (Cometary Sampling and Composition) experiment, which can detect and identify complex organic molecules.

With this data, scientists are hoping to answer the question of whether life on Earth was seeded here by comets, carrying the left-handed amino acids that are present in all life on our world.

If there’s any power after that, the teams will do everything they can to save the probe.

“We’re thinking about two different ideas with the lander,” Lommatsch said. “One is that we might rotate solar panel one, the larger panel, to try to catch more Sun, as it looks like there might be shadow in panel two.

“An alternate that we’re thinking about is running the lander gear up and then hoping that maybe we can bounce our way out, but it’s very unlikely.”

Yet another solution the boffins are mulling over would be reactivating the flywheel that helped Philae to land.

“Powering up the flywheel is a very attractive idea, to spin up the flywheel and kick the lander somewhere – we’re still thinking about this,” Ulemac added.

As for when the team will know for sure that Philae is dead? That’s not so clear.

“If we get to the time to link and we don’t receive any data, it’s prob because the battery’s flat – or some asteroid fell on Philae!” Ulemac joked.

“[But] we can still hope that as the comet approaches the Sun, at some stage we may wake up again,” he said. ®