This article is more than 1 year old

Printing the Future: See a few of UK’s 6.2 million 3D-printed ‘things’

The Science Museum examines additive manufacturing

Best thing since sliced bread, or a technological appendix?

Cautious comments like these are in marked contrast to others, expressed in the consumer section, which seem to suggest we’re on the verge of utopia thanks to 3D printing in the home.

There was much the same kind of buzz around laser (2D) printers back in the mid-1980s, as it became clear to a number of pundits and punters that here was the technology that would ‘democratise’ the publishing business by allowing ordinary folk to create newspapers, magazines and books at home, right from their own personal computer.

This is the same notion that drives many a proponent of 3D printing: that it will take the power of production away from the corporations and put it in the hands of the people.

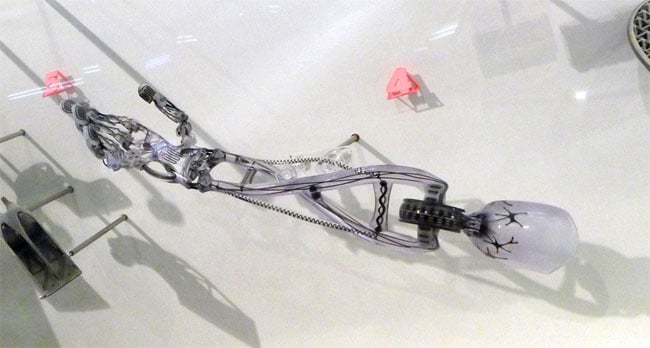

Liberator shows the limits of 3D printing

They haven’t learned from history. The early laser printers were unable to match the quality of a printing press. It took them decades to evolve that far, during which time expensive but high quality output became the province not of the people but of a new breed of output bureau. With it the economics of print changed, and we’re now at the stage where you don’t need to print your publication on a laser printer and hand-staple it - you get it printed online.

Assuming, of course, that you print it at all. It wasn’t low-cost printing that gave World+Dog the ability to publish at will: it was the web, a technology few could conceive in the mid-1980s and even then not as the truly democratic medium it has become today.

There seems little understanding in consumer 3D printing world is aware that some other approach or business model could yet emerge to supplant it. Creating good 3D computer models is as hard to do today as designing good magazine layouts was in the 1980s. Sure, the software tools were there, but what was lacking in many of their users was the skill to use them effectively. That’s just as true of 3D printing now.

Are we about to see a mass of 3D printed objects that are the poorly designed equivalents of all those desktop published pamphlets full of enormous drop-capitals, unsubtle drop-shadows and clip-art? So many 3D printed objects are already becoming clichés of the form.

Is 3D printing’s reach not up to its grasp?

3D: Printing the Future ignores these, more negative scenarios. Here’s another. As we’ve seen with the rise of online ticket sales, we’re now expected to not only pay for tickets but to print them ourselves too. How soon before products cease to be available as physical goods – no one’s visiting the High Street nowadays, in any case – and you have to buy a new pair of trainers as a download to churn out on your home printer?

No need to worry: “A factory can churn out lots of identical items much more efficiently [than 3D printing can],” says Econolyst’s Phil Reeves. “3D printing’s edge is making detailed one-off items that can’t be made efficiently other ways.”

Indeed, the exhibition does include some 3D printed items that really shouldn’t have been. There’s a 3D printed balloon dog - surely making it out of, well, balloons would have been easier, cheaper and taken less time?

There’s also a very fine near full-size model of a radial aero engine, cut away in places to show the pistons and driven by a hand crank. Impressive, but of course while it’s made from 3D printed parts, they still needed to be manually combined into the final working replica. Elsewhere, a pair of mechanical hands rely on strings and wires, added later, to operate. Again, the limits of 3D printing are tacitly shown.

What about the handful of 3D-printed music box mechanisms on show? Alas, they’re kept within a glass cabinet so we can’t see what tune they play. Their delicacy and do-not-touch display suggests they wouldn’t take kindly to rough handling, something of a problem for many a product suggested as a candidate for 3D printing.

Is it though?

And then there’s the Liberator, widely hailed a year or so ago the first gun to be constructed from 3D printed parts. The exhibition presents it complete - or should that be ‘incomplete’? - with its mangled, bullet-torn barrel. Here is an application for which 3D printing is not yet, if it ever will be, applicable.

Perhaps 3D: Printing the Future’s most telling point are two statistics it presents, separately. First, in the past 12 months 3D printers have churned out “an estimated 6.2 million things in the UK alone”. Second, “in the UK alone around 4.8 million 3D printed things are made by enthusiasts each year.”

In other words, fewer than 20 per cent of the output from British 3D printers was generated by manufacturers and others with a real application in mind.

3D printing may well be the future of manufacturing, but for now it’s a hobbyist’s toy.®