This article is more than 1 year old

Bletchley rebooted: The crypto factory time remembered

High commands and dirty words in German – the story retold

From brains to machines

I move out, to the rear of the mansion – the water tower and red brick and whitewashed cottages. The tower briefly hosted a radio receiver but was closed, lest its radio antenna and signal draw attention to Bletchley.

Here I learn Bletchley processed up to 20,000 messages each day from Enigma and later German machines. Messages were dispatched to London and PM Winston Churchill via motorcycle courier equipped with side arm. Later a teleprinter was used, attached to phone line – but no leaky radio signals.

These cottages initially housed Turing and mathematician Peter Twinn among others. Twinn cracked the first Enigma message for Bletchley after just four months, using brainpower and mathematical logic - the code-breaking machines Bletchley is known for had yet to arrive. His work had been informed by information given to Britain by Polish mathematicians who’d obtained Enigma machines and codes before the German army invaded their country. You’ll find a book-shaped stone memorial to the Poles in this area.

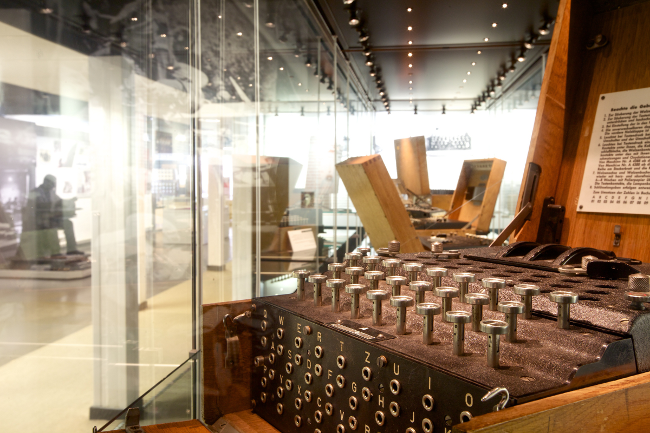

The Enigma machine: first phase in a crypto arms race

On the adults' tour, we also learn of fellow mathematician and code-breaker Gordon Welchman. He headed up Hut 6, breaking the daily settings of the Enigma machines used by Hitler’s air force during the Battle of Britain. Hut 6 sent its information to Hut 3 separated by a distance of just eight feet, where messages were translated, interpreted and dispatched. Messages were passed in Heath Robinson fashion between the huts using a wooden tray tugged along a runner via two pieces of string. The set up was built by Bletchley’s carpenters. Foyle interrupts these observations to say Hut 6 was “inundated” with German radio comms during the summer of 1940 - the start of the Battle of Britain.

It's here I get an insight into how the people breaking the codes worked. Each person was given just a fragment of each individual message – nobody ever got a complete cypher - to maintain total secrecy. “I was aware it was German codes, I was aware it was the Enigma machine, I was unaware of the content,” Hut 6 code breaker Oliver Lawn says on the guide.

All well and good, but Bletchley was under enormous pressure to speed up the decoding. The German military used Enigmas on 100 different communications networks and - to complicate things - they changed the settings of the Enigma rotors each day. The German navy, meanwhile, had gone a step further by customising its own set of Enigmas with the addition of extra rotors and an additional set of codebooks.

The answer was Bletchley’s first code-breaking machine, the Bombe, an electro-mechanical device designed by Turing and Welchman. Actually, Turing wasn't quite the invincible genius received wisdom tells us he is: Turing’s first version of the Bombe didn’t work properly when it arrived in March 1940 and it took Welchman fiddling with the wiring to get things going properly.

The Bombe looks like a telephone switchboard filled with 180 coloured drums. Each drum represented three Enigma machines. Two hundred Bombes were built but none remain – instead you can see a replica at Bletchley.

The Bombe worked by process of elimination, searching for the daily Enigma settings by looking for common phrases. Its results were fed into a separate Typex machine – a kind of typewriter operated by a human who chewed through the Bombe's results to spit out the decoded message at the other end.

Common phrases were recorded on boards, written using coloured children’s crayons that happened to be laying around at the time and that stuck – green for the army, red for the air force and blue for – yes - the navy.

Turing's Hut 8 peeks out from behind code-breakers' Hut 1

The Bombe operators were all WRENs - they also operated the later Tunny and Colossi. WRENs connected plugs and wires to create a spaghetti junction. Then they had to simply wait for the process to stop running.

Turing, I learn, dedicated himself to cracking the German navy’s particularly fiendish flavour of Enigmas from his office in Hut 8, which you can visit. Something was missing, though: those decoding the navy's Enigmas needed the codebooks. One codebook was stolen in May 1941 and but the German navy went and added yet another rotor, making the codes unreadable again.

History took a turn in February 1942 with the acquisition of an updated codebook, and that's where the Bletchley kids’ tour out-guns the adult version. There's a Commando-comic style animation telling how German U-boat 559 was intercepted and attacked by ships of the Royal Navy and how the code books for its Enigma lifted without the German military ever finding out.

It’s a story of luck, daring and heroism as we learn that two crew from one of the warships that captured the U-boat – Able Seaman Collin Grazier and Lieutenant Anthony Frasson from HMS Petard – went back into the sinking vessel for a second tranche of codebooks but they went down with the boat when it suddenly sank. The men earned posthumous George Crosses.

It's these individual tales that come through in the guide and tell a story beyond the headlines of Alan Turing and the Colossus.