This article is more than 1 year old

Tracking the history of magnetic tape: A game of noughts and crosses

Part Two: 'Tis a spool's paradise, t' be surrrre

What's in store?

Tape being tape, the capacities of the numerous cartridge formats that appeared could vary just on how much was on the spool and was often misconstrued as an indication of the data density. Yet one thing was pretty clear, the convenience of and capacity of cartridges had put an end to the reign of the open reel tapes that began this spool’s paradise for data storage.

To get a flavour of the formats that have driven computers old and new, National Data Conversion – a company that handles shifting data from obsolete media – has a neat summary of bygone formats.

While not necessarily fashionable, tape’s usefulness for storage remains, what has changed are its applications. In the home and the office, the rise of the floppy disk delivered improved speed and convenience even if the capacity was a fraction of what tape could offer. Moreover, the falling prices and increased capacity of hard disk drives and now SSDs, has diminished tape’s visibility further still, as it retreated from the office and returned to its spiritual home, the data centre.

Here, tape’s robustness for long-term archiving and its mobility for off-site storage for disaster recovery scenarios has never been in question. However, the use of tape for long-term planning, has like any other digital format, raised issues of compatibility. Progress brings with it legacy formats to accommodate and while we have yet to see a complete consolidation of tape storage solutions, the options are certainly fewer than in years gone by.

One format with legs and no stranger to the data centre was Digital Linear Tape (DLT). Developed by DEC in 1984 and originally called CompacTape, DLT was bought up by Quantum a decade later and by 2006, the DLT-S4 format had notched up an 800GB capacity on 1/2-inch tape. A year later, in order to increase market share, Quantum shifted its focus to the Linear Tape Open (LTO), a tape format that emerged from a consortium originally consisting of HP, IBM and Seagate.

Over the years, many companies have offloaded their tape interests as the writing was on the balance sheet and there has been a decline of fortunes for tape. While necessary for some, this withdrawal may have been shortsighted given the emergence of new big data sources in recent years. It's no longer banks and insurance companies that need this sort of storage capacity and longevity. Big data's momentum has yet to be truly felt by the remaining tape vendors, but they probably do have reason to be optimistic.

The names HP, IBM and Quantum now grace the pages of LTO site along with format licensees Imation, Fujifilm, Maxell and TDK. Recently, TDK declared its exit from the data tape market by March 2014. By contrast, StorageTek, the tape system developed by Sun and now owned by Oracle, recently announced the T10000D tape drive with an uncompressed capacity of an 8.5TB on 1/2-inch tape.

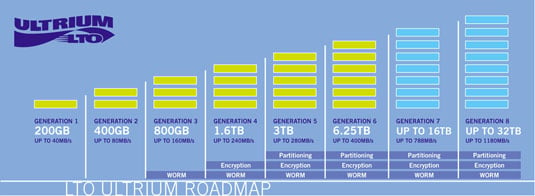

The current LTO Ultrium 6 tape has a capacity of 2.5TB raw (6.5TB compressed), not the 3.2TB raw and 8TB compressed spec that was mooted earlier in its development. The roadmap for LTO 7 (6.4TB raw, 16TB compressed) and LTO 8 (12.8TB raw, 32TB compressed), will deliver substantial capacity increases, assuming there are no tweaks to the spec here either.

LTO Ultrium format roadmap 2012: still some way to go to match StorageTek's latest – click for a larger image

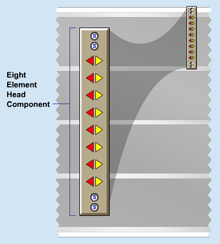

Even so, these promised enhancements are still some way off what StorageTek is offering today and IBM’s 4TB 3592 cartridges for its TS1140 drives. This mix is no bad thing. It demonstrates how tape as a storage medium has certainly not reached the end of the reel. Companies such as Fujifilm continue to develop new tape formulations with finer particles, new bonding agents, thinner tape (for better head contact) and innovative blends of magnetic material.

For the big number-crunchers there are the tape libraries too – robotic tape-switching loaders pioneered by IBM with the 3850 "honeycomb" first unveiled back in 1974.

Quantum Scalar 6000 tape library

Tape libraries have come a long way since then and can now be stuffed with tapes to total several hundred petabytes of data storage connected with 8GB/s fibre to a SAN environment. It maybe backroom but it's certainly high tech and El Reg recently covered these machinations in a feature on tape’s role in data centres and disaster recovery.

This loading, recording/reading, removing, reloading approach may seem a bit like a glorified jukebox, but tape libraries have enjoyed a reputation of high reliability. They also provide a convenient way of handling data for multiple clients for backup and archiving by simply using dedicated tapes for their respective storage needs. And some of those clients can be quite unusual.

Bastion of big data

In part one, I touched on my experiences whilst working at GCHQ several decades ago and its use of tape on instrumentation recorders. I’d sought permission to cover this particular topic and received a friendly go-ahead from GCHQ's Press Office.

I couldn’t resist following this up by asking if tape still played a role at the Government Communications Headquarters. After all, the areas of interest may have moved on from analogue signals to digital data, but surely this secret shrine to big data would have a use for tape storage. I requested an interview and although I was refused one, I did receive a reply and was told:

“The Department does use magnetic tape for backup and archive, and in order to overcome the issues of reading old tapes and old tape formats, the Department refreshes its tape storage periodically.”

As if you didn’t know already, when it comes to big data, old and new, the powers that be at GCHQ have got it taped.

In part three ("Video thrilled the radio star", which you can read here), the use of magnetic tape in entertainment is explored from the video-recorder pioneers to the gradual changes in cinema sound that were accelerated by the work of the late Ray Dolby, a name that has become a byword for audio excellence and in particular in relation to magnetic tape. ®

Special thanks to John Watkinson for permission to use diagrams from his book The Art of Data Recording.