This article is more than 1 year old

Rise of the machines, south of Milton Keynes

Computers make a noise at TNMOC

Inside the machine

First, the teleprinter code came in over the air – that’s the wibbly wobbly high-frequency radio noise you’ll hear filling the air of the Tunny gallery when you take the tour. Back in the war, this noise was filtered and converted by hand to paper tape that was stuck together to make a loop that fed over a series of spinning wheels and was read optically.

The Colossi were programmed to conduct a statistical attack on the code to work out the probability of what each letter meant and thereby determine the Lorenz wheels’ start position. This attack was mounted using the valves chewing the algorithm they’d been fed.

The Elliott 903's boisterous teleprinter (centre) lures kids and senior IT execs

Listen carefully, and above the crazy whirling and reeling of wheels and whooshing of tape on the Colossus Mk II you can also detect a hypnotic tick, tick, tick as the wheels complete a revolution; they spin at 40 miles per hour, reading 5,000 characters per second. Colossus could read 10,000 characters a second, but at that speed the tape would break, so 5,000 was the limit. Each click is a single revolution, with each revolution a statistical attack on the message. So, what you’re hearing is computing in action.

Was it worth it? Colossus played a pivotal role in the D-Day invasion: signals between Hitler and Field Marshal Rommel were cracked using the Colossus Mk II to reveal Hitler had bought the Allies’ deception that the invasion of Northern Europe was coming to Calais in 1944; he overruled Rommel’s request to shift elite Panzer troops down to Normandy, a move that could have turned the invasion into another bloody defeat like the Gallipoli landings of World War One. The message was reviewed in Block D, at Bletchley Park by – we’re told – by "very senior members of command".

All told, TNMOC reckons 63 million characters of “high-grade” German communications were decrypted by 550 people on the 10 Colossus computers.

The atmosphere today in the Colossus gallery feels like some stately home filled with the sound of the mechanical ticking and gentle spinning of antique time pieces. However, it wasn’t like that when the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS, colloquially known as Wrens) ran the machines. The noise was the same but the room was hot, humid and - occasionally - hazardous.

This gallery housed a single Colossus machine that was never turned off. The machine ran 24 hours a day and seven days a week because – Flowers believed – as long as the valves were left powered on, they could operate reliably for very long periods, especially if their heaters were run on a reduced current.

It’s assumed the room's doors remained shut and windows closed owing to the blanket of secrecy that smothered Bletchley, and also because of the night-time blackout that everybody had to observe during the war.

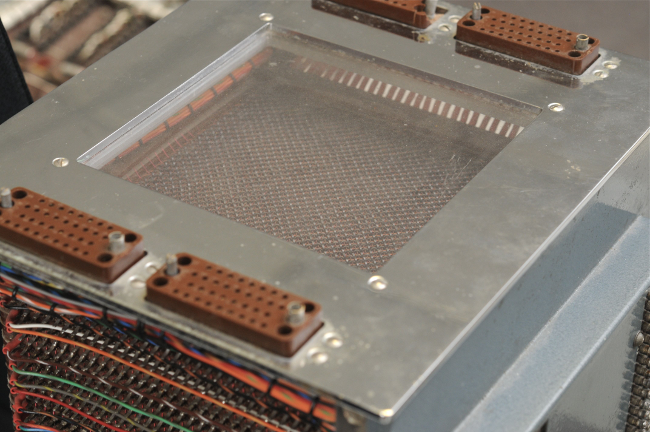

So solid: 20Kb of memory represented in metal mesh and 160,000 hand-made rings

That meant things got hot and humid. In true stiff upper lip fashion, the brass permitted the Wrens to remove their jackets and roll up their sleeves as a concession to these uncomfortable working conditions. They were the only Wrens allowed this level of undress - you can see them here.

Once a leak flooded the room housing Colossus No 9 with water, something that would have been dangerous to machine and the Wrens - for different reasons. This flood is believed to be the source of a persistent myth that water was poured on the floor to try to keep temperatures in the room down.

We leave the dedicated galleries and head to the post-war world, and run into more valves: 829 of them, to be precise. That tungsten-coloured glow represents the computing power running the world’s oldest working digital computer: the Harwell Dekatron Computer, or WITCH, recently rebooted following a four-year renovation.

The WITCH is really a 2.5-ton calculator that ate numbers and spat out answers to complex calculations for the Atomic Energy Research Establishment. It was meant to be more reliable than a team of mathematicians punching away at calculating devices.

Past the WITCH, things start to get more hands-on as we hit TNMOC’s three Elliotts, from Elliott Automation. The Elliotts mass produced in the 1960s and 1970s, with hundreds of units sold to business and academia, before the company was subsumed into ICL, GEC and British Aerospace through a series of deals.

The Elliotts boasted several unusual features and a number of firsts. The 803 is believed to be the first all-transistor computer used in the UK. It featured brand new magnetic cores for logic gates as well as for memory – of which it packed a mighty 20Kb. The 803 used magnetised 35mm film tape from Kodak for storage, and boasted the ability to plug into the mains power supply because, unlike its predecessors, it had dispensed with the need for a special power supply that juiced up the voltage.

Disc evolution: a 200MB slab of storage and its smaller descendants

It’s four cabinets’ worth of computer, with a reader and copier, an operator console – no monitor – and a plotter added to the set up in the 1960s. Next to the plotter lies a sheet of paper with a picture of a Kingfisher produced by the Elliott that looks like it was made on a kids’ spirograph - proof the Elliotts are still in use at TNMOC and evidence that a large number of Elliotts were used in design work, as well as for crunching numbers.

Peek inside a clear-sided cube on top of the 803 and you can see the 20Kb of solid-core memory: a matrix of crisscrossing wires intersected by 160,000 hand-made rings that changed to zero or one when a current was applied. Retrieving data meant scrolling through the Elliott’s 35mm magnetic storage tape, which could take up to 15 minutes.