This article is more than 1 year old

Drilling into 3D printing: Gimmick, revolution or spooks' nightmare?

Top prof sorts the hype from the science for El Reg

The challenges facing 3D printing even though it is more and more accurate

Deloitte conceded that 3D printers are improving in accuracy enough to be able to make objects with moving parts; it also registered that 3D printing is "extremely useful for creating prototypes, highly customised items or small production runs". However, the firm went on to list the following home truths:

- 3D printing can mostly only fabricate relatively homogeneous objects made up of a small number of distinct materials. Printing out small, really complex electronics, or with multiple materials, remains tricky.

- The products of 3D printing are not as durable as conventional products.

- Production runs with 3D printing "do not scale well beyond 10 items".

- Using a 3D printer "tends to be extremely expensive".

Perhaps Deloitte was a little harsh. It could, however, only be right to argue that while some of 3D’s limitations "will be overcome in the medium term", others "are the result of fundamental constraints that are unlikely to be resolved".

3D printing is no gimmick and it will certainly change important dimensions of manufacturing. It is good for customised products and, working hand in hand with other technologies, can bring about remarkable results. But neither SMEs, nor 3D printers, can reinvent or revolutionise manufacturing. Despite their numbers and their populous employee base, SMEs never dominate a developed capitalist economy the way large, multinational, capital-exporting firms do. And 3D printers simply will not have the clout or the versatility that attended the development of, say, the personal computer.

Like the categories of nanotechnology and robotics, 3D covers a vast range of different techniques: if you register on the website MakePartsFast.com and use the "3D printer selector" tool there, you will see dozens of pages of different printers, listed by supplier, "build envelope", market sector and printing material. However, 3D printing is a manufacturing technology that must both work with and compete with other wide-ranging technologies such as nanotechnology and robotics. For example, 3D printing must vie with other methods of prototyping and testing, such as Caterpillar’s "immersive visualisation", which enables earth-shifting equipment to be designed with the aid of a "virtual cab" that is climbed into like an aircraft simulator.

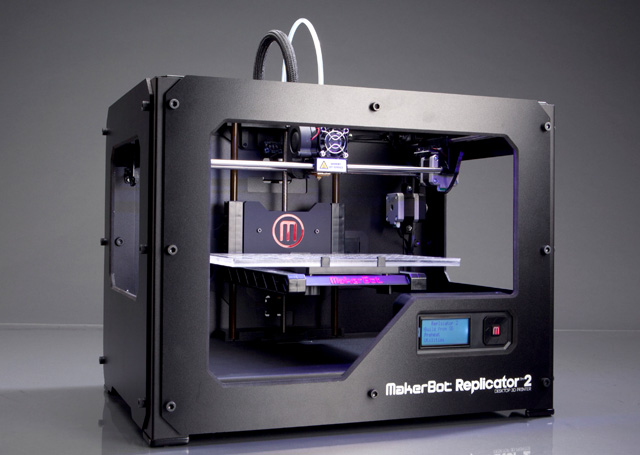

The Makerbot Replicator 2: Copy'n'paste engineering

To do justice to 3D printing, it needs to be seen clearly, without rose-tinted spectacles, and in perspective. Let’s therefore now add a little more historical and contemporary perspective to the technology’s apostles, before dealing with those who, conversely, fear 3D printing today.

Automated machinery inaugurates a new era

Behind the rise of euphoria about 3D printing lies not just experiences with the web and a desire to revive indigenous manufacturing. We need also to recall, first, that America, land of the car, inventor of the assembly line and inventor of the sit-down strike, has paradoxically long dreamt of independent producers as an alternative to factories and mass production. It’s here that the subtitle to Rheingold’s Virtual Community, published 20 years ago, is very notable: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier.

Growing your own IT, and now growing your own IT-based manufacturing with the help of 3D printers, has more than a whiff of the frontier American farmer of the nineteenth century. Of course, small firms, not just homesteaders, figure prominently in the new era thought to be inaugurated by 3D printing. Nevertheless, in a mass property-owning and share-owning economy like the US, it is the householder, perhaps aspiring to run a small and eventually a large firm, who has long been the ultimate hero in accounts of the future that centre on production technique. In his 1980 bestseller The Third Wave, for example, the renowned US futurologist Alvin Toffler famously coined the phrase "prosumer" to describe consumers who, he believed, would more and more engage in production.

Toffler, an ex-member of the Communist Party of the USA, was one of the first to promote the mirage of the mass, cheap, batch production of differentiated products, with consumers specifying designs as their fast-changing lifestyles demanded. Around the same time, French left-wingers and others declared the end of what they called "Fordist", uniform production and homogenous products. In place of these things, they said, had come post-Fordist, "flexible" manufacturing with specialised, heterogenous outputs. Nobody mentioned 3D printers, for it was only in 1986 that Chuck Hull first patented "stereolithography", a process in which a computer-directed beam of ultraviolet light is used to solidify liquid plastic. Nevertheless, the theoretical ground-rules for today’s 3D-printer cultists were firmly laid.

Of course, the technical possibility of automating production to make customised products at low cost is greater with 3D printers and other technologies in 2013 than it was in the Eighties. However, just as another app on your mobile phone tomorrow does not foretell a new era of buoyant, innovative capitalism, so does another thousand 3D printers sold over the web not usher in a new mode of production. It is social and political relations, not the supposedly all-powerful influence of technology, which establish wholly new structures for creating wealth.

In the late Nineties, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), whose Media Lab was, as Anderson notes, the first to rhapsodise about atoms and bits, argued that the web could bring about a radical change in economic regime. In the pages of a late-1998 Harvard Business Review, MIT’s Thomas Malone and Robert Laubacher suggested that the US auto industry had already moved toward a new economy of individual "e-lancers" – one in which temporary, autonomous and self-organising coalitions of car designers and engineers could become multi-millionaires overnight. In the US automotive industry of the mid-21st century, the two academics argued, "while much of the venture capital goes to support traditional design concepts, some is allocated to more speculative, even wild-eyed ideas… A small coalition of engineers may, for example, receive funds to design a factory for making individualised lighting systems for car grilles".

These different conceptions of IT-assisted individualism, each more facile than the last, might be thought to exhaust the homesteading ethos, and certainly should guard us against the sillier extremes of the Maker Movement. But there is more. In the realm of energy, hopes of a kind of hardy independence from electricity networks, powered by solar panels and other renewable energy sources, have bolstered the idea that, if "the personal is the political", then the domestic can also be economic.