This article is more than 1 year old

Schmidt still scanning the skies 50 years after defining the quasar

El Reg talks with legendary astronomer about gamma rays, GPS, and Hitler

A shift in time

Schmidt spent long nights at Southern California's Palomar Observatory zipped into an electrically-heated flight suit against the killing cold, studying radio emissions in space. He soon grew intrigued by the huge sources of energy he saw there.

NASA's estimation of what a quasar could look like

Fellow astronomer Tom Matthews had begun to measure the redshift of these radio sources, and was getting results that suggested that they weren't as close as had been thought, but instead light-years further away. But the problem was that under to the prevailing view of the universe as being in a steady state, expanding constantly but with an even mix of matter inside, this wasn't possible.

Quasars exist only far back in cosmological time and aren't evenly distributed, as they would have been under the steady state theory of the universe that was then championed by such prominent figures as Sir Fred Hoyle. Quasars are a much better fit in the Big Bang theory of the universe, where certain types of objects form at specific times in the universe's growth cycle.

"Some prominent astronomers formed the opposition and would not believe what was going on," he explained. "But I liked Fred very much, we were certainly good friends. He was fantastically original and intelligent and extraordinarily creative."

Guiding lights

All this might sound very esoteric but there are plenty of practical applications to Schmidt's quasar discovery – not least the possibility of GPS here on Earth.

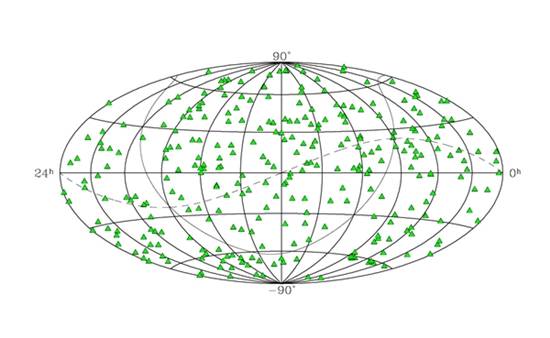

Because quasars are so far away, they are incredibly stable in their positioning, and as some of the brightest objects in the sky they are easily recognizable. In 1995, NASA completed its first International Celestial Reference Frame (ICRF) map of 600 quasars, now has over 3,000 logged in, and the map is the fundamental reference system for astronomy positioning.

The precise mapping of quasars has applications on Earth and beyond

The position of these quasars is used to guide GPS satellites as they encircle the Earth from precise points to coordinate data. Thanks to the work of Schmidt, quasars are their guide-points, and their emissions could conceivably be used as navigational markers for space travel as well.

Quasars are, however, a dying breed. They appear to be a feature of the early life of the universe when there was plenty of fuel for the black holes thought to drive them. After 30 years of study, Schmidt is devoting the latter part of his career to the study of gamma ray bursts, mysterious bursts of energy from back at the beginnings of the universe.

Gamma ray bursts were first detected in the 1960s by US military Vela satellites, which were lofted to keep an eye on the Russians and make sure they weren't breaking the nuclear weapons test ban. They detected the gamma radiation from a distant point in the universe, and it's now thought that these bursts are generated by supernovae or the merging of stars.

At 84 Schmidt is still going strong, although he said that he appreciates the use of CCDs in the field, since it means no more long nights sitting in damp fields or on frigid mountain-tops. Eventually he says he'll be forced to retire from Caltech, but that won't stop his sky-gazing.

"Astronomers are among those who you never know when they are retired or not because we keep at it," he said. "All astronomers love the work they are doing – they are dedicated, and perhaps even obsessed." ®