This article is more than 1 year old

The Oric-1 is 30

The colourful story of a would-be Spectrum killer

Target: Sinclair

The start of the home micro project didn’t mean the end of the Tiger, at least not yet. Come August 1983, months after the low-cost machine had already gone on sale as the Oric-1, Tangerine announced the TD-3000 Tigress with a view to shipping the machine the following October. By then the design had also been sold to HH Electronics, a developer of audio amplifiers founded in the late 1960s and based just down the road from Tangerine. HH announced the HH Tiger around the same that Tangerine did, before putting into production later that summer. HH would take the risk and considerable cost of tooling up for Tiger production off Tangerine’s shoulders.

PCN’s reviewer, Susan Curran, called the Tiger “the Rover of the micro world perhaps”, but the computer failed to make an impression, despite its novel architecture. It was too costly to produce, and Tangerine was never able to ship its version, the TD-3000. HH’s parent company went bust three months later and that was that. Meanwhile, rather than release the micro that was by April 1982 already called the Oric - the name, conjured up by Tullis from a partial anagram of ‘micro’, confirms Paul Johnson - Tangerine instead chose to establish yet another company, Oric Products International, to take the computer to market. A key source of funding for Tangerine’s new computer was secondhand car seller British Car Auctions (BCA), brought in by Tullis, who knew BCA founder David Wickins. Wickins was persuaded to invest in the UK home computer boom and put up £350,000 to fund development work, but this was contingent on the establishment of a new company to market the micro.

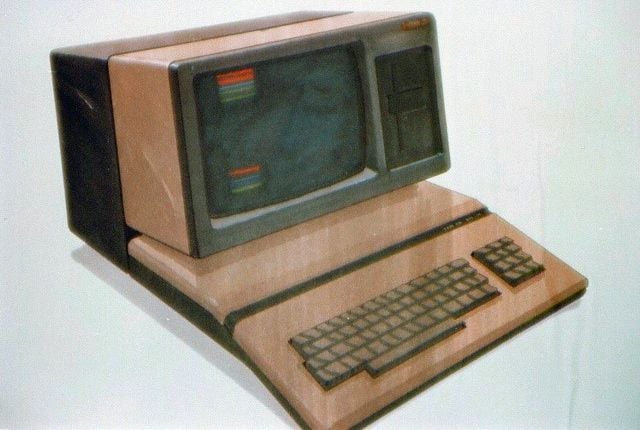

Tangerine's early visualisation of the Tiger

From the collection of Paul Kaufman

Tangerine’s role, then, was to develop the machine and license the design to OPI, for which it charged £100,000 up front plus 50 pence per unit for the first 100,000 units, recalls Johnson - £150,000 in all. Indeed, the computer’s motherboard would clearly state: “ORIC-1 Designed by TCS Ltd”.

Tullis became OPI’s Chairman, with Johnson and Barry Muncaster taking on the roles, respectively, of Technical Director and Managing Director. Peter Harding was put in charge of sales and marketing, a role he also fulfilled for Tandata. OPI’s remaining director was Ted Plumridge, present to represent the interests of BCA.

Having designed the Microtan 65 around the 6502 processor - the version of the chip produced by Rockwell - Johnson decided to use the chip in the Oric too. The home micro needed to be developed quickly and cheaply, and that mean using as much of the Microtan as possible.

Designing the Oric

“We stuck with the 6502 processor... because it's probably the world's best-selling chip,” he said in an interview with Popular Computing Weekly published just after the Oric’s formal launch in January 1983. “Besides we have lots of experience with it, and software for it has already been built up. For example, we can quite easily modify the Microtan DOS to run on the Oric.”

Development work ran through the spring and summer of 1982. In July, Tangerine told the press it had completed the design work on “a new micro which will go on sale in October for less than £100” to take on the Spectrum, which by then had still not shipped in volume and, it was becoming clear, would not do so until the following autumn. Central to keeping down the cost was the use of a monolithic ULA (Uncommitted Logic Array) chip - what today would be called a Gate Array - designed to combine as many subsidiary logic components as possible.

“Incorporating the ULA into the Oric enables the price to the customer to be considerably less than in computers which use generally available chips and processors,” claimed Peter Harding in the June/July 1983 issue of Oric Owner, the by-then rebranded Tansoft Gazette. “The Oric ULA takes the place of 80 chips which would normally be needed to do the job it does.”

According to Paul Johnson, the ULA was originally created as a TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic) integrated circuit. “Once you have the TTL version working, you know the logic is OK,” he told Popular Computing Weekly. Tangerine used the TTL ULA emulators in the first Oric build. However, the final machine would use CMOS chippery, fabricated by California Micro Devices - which, in 2010, would be absorbed by industrial chip designer and manufacturer On Semiconductor. “CMOS technology is different from TTL, so we first laid the thing out as a plan to see where the problems would be,” said Johnson in 1983. “Then we did a simulation of a new logic diagram and worked out the timing paths.

“When the first finished gate chips came through from California Devices in early December we took out the emulator, plugged in the chip and it worked first time. It was quite a relief!"

Inside the machine

Alongside the ULA and the 6502 sat a General Instruments 8912 sound chip - audio would prove to be one of the Oric’s strengths, as would the graphics - and a bank of Ram chips, 16KB or 48KB depending on which version you chose. It contained 16KB of Rom. The Rom chip was allocated to the top 16KB of the Oric’s 64KB memory map. The Ram was segmented into, first, four 256-byte pages and, at the top, 10KB of memory for the high or low resolution displays - 240 x 240 pixels and 40 x 28 characters, respectively - and standard and Teletext character sets, copied in from Rom and so editable by the user. In between, sat either 5KB or 37KB for program and data storage.

Connectivity with the outside world was provided not only by the inevitable UHF modulator but also five-pin DIN port to pump an RGB video signal to a monitor, a feature serendipitously added by Johnson because he had some suitable components going spare. This would ensure the Oric-1’s supremacy in France - all it took to support France’s SECAM-format TVs was a cheap RGB-to-Scart cable, which produced better results than the expensive PAL-to-SECAM active adaptors other UK micros needed. A second, seven-pin DIN served as the cassette feed.

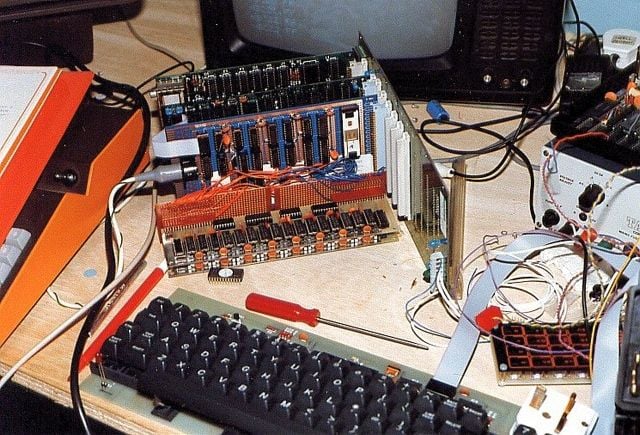

Early Oric prototype hardware

From the collection of Paul Kaufman

“What marks the Oric out from some of the older machines is that it has been designed with an awareness that 1983 will see computers being used increasingly for practical purposes,” said Meirion Jones, reviewing the Oric-1 for Your Computer’s February 1983 number. “The built-in Centronics interface will make it easy to plug in a printer or other peripherals. Oric will soon be selling a modem so that Prestel will become available.”

Tangerine’s own expansion bus port completed the Oric’s port array, set into the back of the machine behind its 57-key plastic capped keyboard, a kind that today might be called calculator-like, but back in 1983 was praised for being not only laid out to make typing accurate but also for avoiding the Spectrum’s rubbery ‘dead flesh’ feel. Unlike the Sinclair machine, the Oric had a space bar. The keyboard, along with the entire casing, was created by industrial designer Paul Durbin, who would go on to style OPI’s later micros.