This article is more than 1 year old

Scottish Highlands get blanket 3G coverage

... It's a teensy blanket though: El Reg compares femto offerings

Femtocells, which extend 3G networks using domestic broadband, have been around for a few years now, and while only one operator will take your money for one, the others will furnish you with one if you complain loudly enough. Now that most of the big UK providers each have their own gear, we thought we'd see whose tiny cell offers the biggest service.

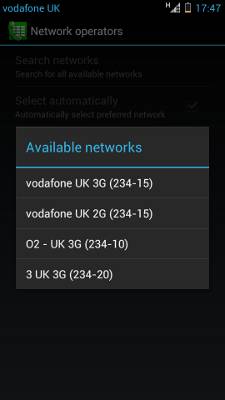

With femtocells from Vodafone, Three and O2, even our Highland bureau can experience 20th Century connectivity - even if the majority of Scots can't. The boxes are tiny base stations connected to the network operator over domestic broadband, enabling customer to pay twice for a service it would be impossible to receive otherwise.

That's if the customers can get a box. Vodafone sells its new Sure Signal box at £100, but the other operators restrict distribution to disgruntled customers - threaten to leave and, if you're a good enough customer, they'll send you one gratis. EE wasn't able to get us a box to test - the company is still working on the technology though we understand it has boxes in the field - but we did get femtos from all the other UK operators.

The 2G signal is macro, the rest is all femto

A femtocell is a base station - a full 3G cellular base station - with enough intelligence to find itself an available frequency and secure connectivity back into the operator's network.

Finding a frequency means listening to the macro network for bands which aren't being used locally, something which took up to six hours on the first Sure Signal box from Vodafone but has improved markedly since then. All the boxes require one to register with a postcode, which speeds things up but isn't rigorously enforced, and phone numbers have to be registered too, with all the boxes supporting at least eight numbers.

In our experiments, the "Home Signal" box from Three booted most quickly, getting up and running within 10 minutes, though it also had trouble running in the same room as the other two - complaining of too much interference. Vodafone's Sure Signal wasn't far behind, being ready to go within 20 minutes. The laggard was O2's Boostbox, which took around an hour to indicate it was ready to route calls.

Three, Vodafone and O2: You can plug something else into the Vodafone socket, but irons aren't recommended

The Three box is, to our eyes, the most elegant, with a single LED showing solid green when operational, blinking green when a call is connected, and flashing red in coded patterns when something is wrong (such as three flashes to indicate the aforementioned interference). The other two boxes have separate lights for power, successful connection to the internet, successful handshake with the network operator, and phone connections, the combination of which can indicate any problem with the process.

Vodafone's box is very new. Using chips from Broadcom, it's built into a hefty plug and looks like a Powerline Networking box. Indeed, we had heard it would support Powerline Networking, but it seems that's not supported, yet so we plugged in an Ethernet cable just as we did for the other boxes.

O2's Boostbox is what one would expect from O2, looking more like something one should put on display than networking hardware designed to vanish into the background.

Enough aesthetics... Do they work?

The hardest part of the process is, without doubt, registering the phones you wish to use. That's done though an operator portal and requires you to log on and provide the serial number from the back of the femto along with the numbers to be registered, but the services clearly suffer from a lack of use. Vodafone's failed entirely when we tested, forcing us to speak to a human who managed the process manually.

Once they were set up, all three boxes work fine, routing calls and 3G internet connections without difficulty - but beyond the basics, performance did vary.

All the boxes were tested over the same broadband connection (a microwave link going to an ADSL connection at Claire's house) which was clocking in at 4.8Mb/sec down and 370Kb/sec up with a ping of 50ms.

The ping was the biggest differentiator, which isn't surprising as 3G is known for its high latency. Having said that, O2 repeatedly achieved half the time of the other two, with a ping averaging 173ms compared to Vodafone's 373 and Three's 337.

But latency isn't everything, and O2's throughout of 2.5Mb/sec was put into the shade by Three, which achieved speeds nudging 4Mb/sec, with Vodafone falling between the two at around 3Mb/s.

Upload speeds were all around 300Kb/sec, most likely limited by the ADSL connection as 3G (HSPA) should be able to top that easily enough.

Three might have been fastest, but it also had the shortest range with calls dropping out around 40m despite having line of sight. O2's Boostbox managed 55m and Vodafone's new box was still routing calls at 70m when we hit a barbed-wire fence and a flock of disgruntled sheep, so testing was stopped - though the signal was starting to break down and would have dropped out very soon.

All three networks should be able to hand off calls onto the macro networks when one gets beyond the femtocell's range, even if the reverse isn't yet possible, but as the testing was done beyond the range of the macro networks (which is surely where most femtocells will be used) the calls just got dropped.

Tiny cells, evolving

We’ve been waiting for femtocells for a long time now, and while the idea of paying for the same bandwidth twice (once to the mobile company, once to one's broadband provider) seemed unlikely to succeed, the femtocells are multiplying and slipping slowly into a lot of homes.

Femtocell technology is also pushing into the macro network - self-configuring base stations don't need trained engineers to fit them, and smaller cells increase overall network capacity - but the domestic application never disappeared, it just seeped slowly outwards.

EE's reluctance to admit it has a femtocell offering is almost certainly down to its examination of the potential of LTE (4G) femtocells. In the USA, femtocells deployed by Sprint are open - they'll route calls made by any passing Sprint customer - something we'll likely see more of as internet bandwidth gets cheaper and operators develop more interesting business models.

Right now those models are very dull, with Vodafone charging £100 for the hardware and O2 and Three requiring domestic customers to complain bitterly in order to get one - and none of the operators offer any kind of discount to those paying for their own back haul.

But they should be, as femtocells can also forestall those pesky over-the-top players that have their eyes on voice revenues. Smartphone-touting customers who routinely using Wi-Fi at work and home will find VoIP services increasingly attractive, especially if the cellular coverage at either location isn't good, so one might imagine operators would push femtocells harder than they're doing at the moment, especially given that the hardware undoubtedly works. ®