This article is more than 1 year old

James Bond doesn't do CGI: Inside 007's amazing real-world action

Invisible Aston? We don't like to talk about it

Mind the gap...

"One of the biggest things we did was the Underground train," says Corbould. "The biggest challenge was the sheer scale and we only really had one go at it - and it had to be at realistic-looking speed."

Set-up was meticulous: the carriages were constructed using a aluminium, fibreglass paneling and polycarbonate to help minimise weight.

"We knew it couldn't veer off the track," Corbould says, so besides a main train track being built that ran atop a set of goal-post-shaped supports, a hidden monorail was added for the purposes of guidance that ran across the entire stage. The speeding train runs along this, then crashes into the main set, which is built of foam bricks eight feet below the Pinewood stage floor in those massive tanks.

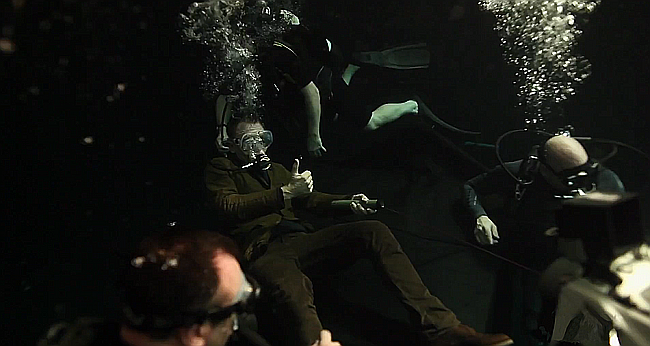

Daniel Craig goes down in Skyfall's underwater shooting, from the Skyfall videoblog

"The second problem was we had to stop the train afterwards, otherwise it would end up in the stage wall. We used a brake system with cap of two tonnes each. We put a series of those in line so it wasn't a dead stop, it was a slowing stop, then 30 tonnes of sandbags to take the real speed out of it."

"In theory we could do it again - but at huge financial cost."

The same might be said of the digger and train sequence. This involved mounting a working, 25-tonne digger on a flatbed carriage moving at 25mph - in the film, the digger's arm is used to span a gap between two separating parts of the train. The digger was wider than the flatbed, so three crushed VWs were installed to act as track for the digger on the carriage. "We had to make sure the digger stayed on the carriage. We built a giant wall to make sure the digger couldn't slide off sideways," Corbould says.

In the 50 years since Dr No, those working on the mechanics of making Bond films have delivered a character that's become as British as the Union Jack, a nice cuppa, and thrashing Johnny Foreigner in the velodrome.

Broccoli and the nation aren't the only fans, as those working on the films have imbibed the spirit and channeled it into the execution of the scenes we know.

Fornof is so passionate he's given ideas to Bonds that he didn't end up filming, thanks to work commitments: the pilotless plane that tumbles over the edge of the cliff at the beginning of GoldenEye – which Pierce Brosnan then skydives into – was a Fornof creation.

"It's all just a matter of gravity," Fornof explains matter-of-factly.

"A person will fall at 120mph. We've done that kind of stuff before. I said why don't you do that, he could go off a cliff. I picked that plane too ... You can put the propeller in reverse - it slows it down."

Fornof's favorite Bond project? Impossible to say.

"I love all of them," the normally plain-talking pilot says, a little romantically. "The're all individual - every one I've done, they all have their stories. I don't know, because they are all like your kids."

How does he rate some of today's Bonds?

"They look good" - but there are some scenes where they could have done a better job on the aerial sequences, Fornof says.

Browning remains a fan, still enjoying Thunderball on TV.

"It was a fun movie to make and watch. I think we did as good a job as we could on Thunderball."

Thanks to Browning, Fornof and Corbould, a literary character from the 1950s has been introduced as a very real and very national character. Most viewers will have first met Bond through the films, without even realizing the books existed, thanks to the bank holiday TV scheduling of the BBC or ITV when growing up or through the box-office assault from the GoldenEye reboot of Bond.

From the martini, shaken not stirred, and the throwaway one-liner ("Shocking, positively shocking"), to the sweat-inducing aerial sequence on the wing or on the crane, we know our man to be cultured, calm and deadly, prevailing over whatever odds the creatives on set throw in his path.

Skyfall producer Barbara Broccoli recently recounted how, growing up with her dad, she too believed Bond was a real person. It wasn't until she was seven that she discovered Bond didn't really exist, she said.

And thanks to the techies behind Bond, the rest of us can still make believe too. ®