This article is more than 1 year old

Australia 'needs' powers to ensure net neutrality

Review suggests new regulatory body, structural separation for broadcasters

Australia needs to change media policy for the digital age, because current arrangements “have outlived their purpose” and “now run the risk of inhibiting the evolution of communications and media services".

That’s the thrust of the new Convergence Review commissioned by Senator Stephen Conroy to examine whether Australia’s media policy and regulations are up to it in the internet age.

And one of the arrangements that need new powers for government is Internet Service Providers' control of content.

In a section of the review on “Content-related competition issues” the document lists “areas where new powers are needed”. One of those areas is network neutrality, which the review says deserves attention because “… there are concerns that internet traffic can be subject to management practices that are designed to limit competition and reduce innovation.”

On unmetered content used as a differentiator among ISPs, the review says: “…the provision of unmetered content may also create competition concerns, where this practice is employed by dominant players in a market to keep out new entrants, or where customers of one ISP are allowed to access unmetered content from one particular content supplier.”

The review, which declares itself unashamedly uninterested in further media regulation, even goes so far as to suggest structural separation, of a sort, for radio and television broadcasters.

“With changes in technology, a new television service could launch with internet delivery without any requirement for licensing, while commercial television broadcasting remains heavily regulated,” the review observes, adding: “This has led the Review to conclude that licensing of content services can be removed. The myriad categories of broadcast services and the separate regimes for planning and management for broadcast spectrum can also be discontinued.”

The proposed replacement is “annual spectrum fees”, an important change from broadcasting licences as the review imagines television and radio broadcasters could devolve to become either content providers or infrastructure providers. Under this regime television stations would not necessarily need to be both a producer of content and the operator of a broadcasting platform. The review believes this kind of arrangement would promote media diversity and improve spectrum management.

Which is not to say the review believes all regulation should be removed. Instead it believes that media ownership should continue to be regulated, to prevent over-concentration of media owners. Prevalence of local content is also deemed worthy of ongoing legislative oversight.

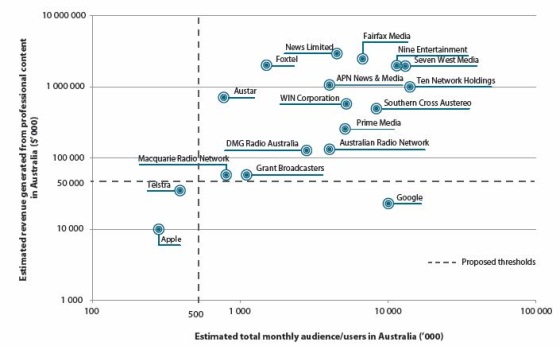

The review also recommends that around 15 media organisations should create and participate in a new body which will supersede both the Press Council and the Australian Communications and Media Authority’s complaint-handling functions. The organisations required to participate in this body would have “$50 million a year of Australian-sourced content service revenue and audience/ users of 500 000 per month” a twin threshold that would see them dubbed a “content service enterprise”. A content service enterprise would also display the following three characteristics:

- they have control over the content supplied;

- there are a large number of Australian users of that content; and

- they receive a high level of revenue from supplying that content to Australians.

Other media organisations wold be “encouraged” to join the new body, which should have “credible sanctions and the power to order members to prominently publish its findings” and would have a role “promoting news standards, adjudicating on complaints [and] providing timely remedies.” But the Review also notes that major players in the distribution of content – Apple, Google and Telstra – don’t make the grade, as illustrated below.

The review does, however, view “content service enterprise” status as attainable, or revokable, meaning Internet companies could make the grade in future.

The review’s plan is very different from the recommendations of the Finkelstein report, which back in March suggested that 15,000 page impressions a year made any online publisher worthy of regulation by a government-funded-and-operated regulator with the power to compel corrections.

The Convergence Review rejects Finkelstein’s approach, saying “a statutory authority that would regulate news and commentary should be an option of last resort available to government. The Review is recommending an industry-led approach that is more likely to produce immediate results and a better long-term solution.”

While the review and the Finkelstein report differ on this new regulator being a statutory body, the Review is comfortable with government funding the new body as a “last resort” measure to ensure it is adequately funded. ®