This article is more than 1 year old

2011 Reg roundup: Hacking hacks, spying apps and an end to Einstein?

Smartphones, privacy and a year of tears

Who's that inside my phone?

Carrier IQ's code was confirmed to exist on devices from Apple, AT&T, Sprint, HTC, and Samsung. Verizon, Nokia and Research in Motion denied reports saying they use it.

Trevor Eckhart, the Android app developer who initially uncovered the presence of the spying app, posted his evidence to YouTube. Meanwhile, Carrier IQ vice-president of marketing Andrew Coward rejected claims that the software posed a privacy problem because it doesn't capture key presses and doesn't report back in real-time.

It seemed Carrier IQ was intended for diagnostics, hence the reporting aspect. Coward told The Reg that data is dumped out of a phone's internal memory almost as quickly as it goes in.

In a world where a single researcher can quickly broadcast his results via YouTube, the handset makers, carriers and the software company are left looking like they have something to hide.

Only in cases of a phone crash or a dropped call is information transferred to servers under the control of the cellular carrier so engineers can troubleshoot the problem. Not that this stopped Washington's politicians from jumping in: while the story was breaking, US senator Al Franken called on Carrier IQ to explain why its diagnostic software isn't a massive violation of US wiretap laws.

Privacy also became easy fodder in a low-scoring battle between tech's big names: Microsoft and Google.

Researchers this year discovered that Apple's iPhone and iPad were constantly tracking users' physical location and storing the data in unencrypted files that could be read by anyone with physical access to the device. Elsewhere, it was found Google's Android can store your Wi-Fi router's precise location and broadcast it for the world to see. Hacker Samy Kamkar said Google was compiling a publicly accessible database of router locations in its goal to build a service like Skyhook, which pinpoints the exact location of internet users who use its sites.

Apple and Google weren't alone, however. It emerged that Windows Phone 7 builds from Dell, HTC, LG, Nokia and Samsung were transmitting info to Microsoft that included unique device IDs, details about nearby Wi-Fi networks and the phone's GPS-derived exact latitude and longitude.

Caught out, Microsoft sent a lofty letter to members of the US Congress in May saying it would stop identifying specific mobile devices that use its location-tracking services. Andy Lees, then president of Microsoft's mobile communications business, wrote: "The location-based feature of a mobile operating system should function as a tool for the user and the applications he or she elects to use, and not as a means to generate a database of sensitive information that can enable a party to surreptitiously 'track' a user."

Google also contacted The Reg to say it's not accurate to say the company collects a "unique identifier" from every phone that informs the company of its location.

Clearly this was a touchy subject. It reminded us of the furore in the 1990s and more recently when Windows was caught "reporting" back to Redmond. In the event, it was information useful for improving security, producing software fixes and ruining software pirates' afternoons - but the fact that Microsoft hadn't been upfront poisoned the atmosphere as the company was entering a browser anti-trust bubble.

Carrier IQ, phone makers and network providers are also now suffering from the same lack of trust because we're now in a world where a single researcher can quickly broadcast his or her results via YouTube. What other hidden code could be lurking inside our smartphones and watching what we are doing?

Diagnostics is one thing, but knowing where you are and what you're doing happen to be two vital pieces of data. The ability to access this information would be a huge boon to those making and selling phones and related mobile services. Social networks such as Facebook and Foursquare rely on being able to monetise such data. Google and Microsoft want to refine context-sensitive ads around it. This means the issue of data privacy and smartphones is an onion that has plenty of layers left to peel.

Neutrinos, Phobos-Grunt and Neil Armstrong's embarrassment

Space and science saw earthly breakthroughs and extraterrestrial setbacks.

Nearly two years ago, the the largest and most powerful particle accelerator on the planet, the Large Hadron Collider, went live. LHC's mission has been to track down the Higgs boson: its existence could help explain why some particles have mass, helping explain the fabric of the universe.

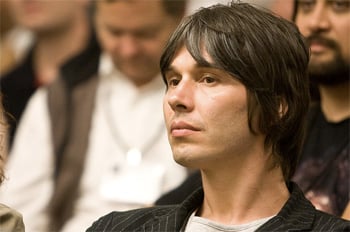

Cox: time-traveling neutrinos taking scientists back to basics

As the year wound down, boffins reckoned they were getting closer to pinning down the elusive boson but the LHC threw up one particular result that had atom-smashers scratching their domes and time-travel fans hunting eBay for DeLoreans.

Physicists working for CERN in September fired a beam of 15,000 neutrinos from Geneva, LHC's HQ, to Gran Sasso in Italy – only to find the particles completed the 730km journey 60 nanoseconds faster than light would have.

Translated: the neutrinos had traveled faster than light, but Albert Einstein in 1905 had said no object could be accelerated to the speed of light. His assertion underpins the theory of space-time and of relativity and it cements our understanding of cause and effect, of past and present – of time travel.