This article is more than 1 year old

Ofcom grills pirates, loses report under fridge for two years

'Music, vids pirated because they're too expensive' shocker!

Analysis On Monday Ofcom published two studies it commissioned into digital piracy: one attempting to quantify the level of piracy, the other a smaller study collecting pirates' opinions.

Oddly, the 'new' quantitative research is old - almost as old as the Norman Domesday Book. The field work was conducted by Kantar Media in March 2010, while the Digital Economy Bill was still being debated, and completed in May 2010, over 18 months ago. You might expect something of such vintage to be called Vagabonds: an Enquiry, and discuss sheep rustling while weighing the deterrent effects of public pillories. Not that we want to be putting ideas into people's heads. Geoff, put that saw down.

So why now, we asked Ofcom. Had they lost the report down the back of the radiator or under the fridge? Maybe down the back of a comfy sofa?

The watchdog couldn't account for the delay, but stressed the two studies were not part of the 'baseline' research that it's obliged to undertake as part of its monitoring duties for the now-forgotten Digital Economy Act. Ofcom's director of internet policy Campbell Cowie is deeply hostile to the DEA, and quite coincidentally nothing's happened. Instead it's about experimenting with methodology.

And that's probably the most interesting thing about the studies. For its quantitative study, Kantar uses three methods: face-to-face interviews, and telephone and email surveys - and we get the chance to compare answers from each. With the presence of an interviewer responders tended to report lower copyright infringement activity online. Kantar speculates that might be because of guilt - or suspicion about the interviewer's agenda. As the firm puts it: "The presence of the interviewer might make people think harder about moral issues, and lead to more considered responses."

Kantar also tried to mitigate against the "leading question". But its own choice of questions is bound to come under scrutiny. For example, we know that the market is more convenience-sensitive than it is price-sensitive: the 'fifty-quid-a-week bloke' is vital to both the movie and music industries. We also know historically the price of DVDs and music has fallen sharply. And digital prices are typically lower than physical prices. But Kantar instead chose to agree with the statement "I find music and video files that you pay for on the internet expensive".

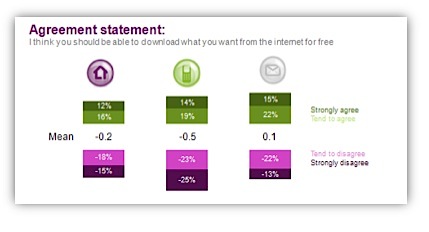

It also asked responders if they agreed with the statement "I think that you should be able to download what you want from the internet for free", but there are no questions about how to make buying more convenient or what such service innovations would do to behaviour. So despite the protestations about question bias, Kantar's results are going to be seriously skewed.

As for the results, there are few surprises. Most people don't download - it's a mere 12 per cent according to the face-to-face polling and 19 per cent according to the online survey. 'Free' downloading is highest amongst the demographics that are time-rich but cash-poor: those aged 12 to 15 and 16 to 24. TV programmes and video games are the most popular media, but there's hardly any difference across eBooks, movies, music and software. Unlicensed downloading is fairly common amongst children aged 12 to 15 in broadband homes, though, 60 per cent have done so in the past three months.

Quizzing the pirates, Kantar found that "agreement that you should be able to download what you want from the internet for free" is split down the middle amongst the general population and amongst general downloaders. It rises considerably amongst peer-to-peer network users, with 56 per cent in favour compared to 25 per cent against.

Kantar: views of downloaders only: infringement is higher in this sample (31 per cent) than general population (12 per cent)

People were asked whether they agree with the statement "music and video files that you pay for on the internet are expensive"; not surprisingly, given the question practically invites the respondents to shout "it's daylight robbery", Kantar concludes: "Agreement is generally high anyway suggesting it does seem to be a prohibitive factor for everyone, regardless of whether the user seeks out free (and possible illegal) alternatives or not."

If that was true, then fifty-quid-a-week bloke would never have existed - and Coldplay, Adele and The Black Keys would have been crucified for shunning the free streaming music services and insisting fans buy the album. They weren't - they charged £7.99 on iTunes and £7.49 on Amazon - both higher than the £7.32 average CD cost in 2010 - and got it.

As we saw with the much-criticised sociological research by the LSE into the causes of the August riots - the answers you get simply reflect the questioners' biases and prejudices.