This article is more than 1 year old

Nokia's Great Lost Platform

Could've been a contender...

Big Bangs

Flexibility is great asset. But flexibility can also be a double-edged sword.

Sometimes when a new platform brings significant advantages, it's advantageous in the long run to move everyone over at once, or as quickly as possible. Product managers and marketing teams must get behind the new platform, without reservation. As the saying goes, all the wood must be behind the arrow.

But if it isn't, then pockets of loyalty may remain around the older, more established technologies. Nokia was a burgeoning organisation, and avoided presenting Hildon as the one true future platform, one that was flexible enough to encompass the others. So political factions arose, and clung to the older, less capable technologies.

As we shall see, Hildon's flexibility permitted the more conservative factions to do this. A risk-averse management culture avoided short-term pain, and long-term gain.

Nokia's intention had been to license Hildon. It viewed Series 60 as a first step: the future of media devices and communicators would be Hildon, according to sources familiar with Nokia’s strategy. As the project neared completion, it was content to wait on the licensing, however.

Nokia had two product families in mind for its new platform. One was media tablets, codenamed MX, and the other a more modern version of its Communicator line, CX.

But things had become complicated. By mid-2003, the landscape had changed subtly from three years earlier.

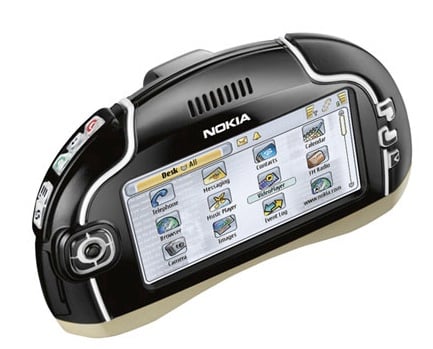

"And this came in looking like Darth Vader's helmet..."

Nokia's first media tablet - and the first Hildon device

During 2000, Symbian was being pulled several ways. The original goal of a crack design team handing designs to the shareholders

“Symbian knew what consumers wanted, what software they wanted,” Millar recalled last year. “But it got pulled apart by competing views – it could never execute on Symbian view.”

It decided upon a strategy called Project Nightingale – a tactical withdrawal from creating user interfaces. Except for the ones it did continue to develop. UIQ, a rival pen-based user interface, potentially useful for tablets remained on an uncomfortable perch in the Symbian nest. (Symbian’s UIQ team, and its principle beneficiary Ericsson, knew nothing of the top-secret Hildon project).

Nokia in particular had become frustrated by the politics of Symbian, but was still supportive of its goals of building a mass market on a common base. It decided to take matters into its own hands. During 2000 and 2001 it cobbled together a user interface for devices that looked very much like traditional phones. Nokia would license this to other manufacturers, but handle the licensing itself. It would evangelise its own APIs, too, thus “owning” the developers and UI. This was announced halfway as the Hildon project reached its halfway stage, in November 2001.

The move allowed Nokia greater control, and the ability to bring its own products to market quicker, the company hoped. Nokia had announced a games console N-Gage, based on Series 60, in 2002 [N-Gage review]

But it also allowed what really was a limited, ad hoc codebase to become entrenched. The first sign of tension was in 2003, before Hildon had been announced to the world. Nokia cancelled CX, the advanced QWERTY keyboard Communicator for which Hildon had been designed. Since it had never been formally announced, most press and analysts were not aware of this.

"It was no big deal to us," recalls Millar. "Instead of CX being the lead product, it was MX. It was the same hardware underneath."