This article is more than 1 year old

Happy 40th birthday, Intel 4004!

The first of the bricks that built the IT world

Getting high, m'K?

Although the disintegration of the P6-Rambus project turned out to be good for Intel in the long run, "It taught us one big lesson: you don't integrate new memory on your processor. You make sure that that memory technology is stable, and that you have a good supply from the memory industry because you don't want to impact shipping your processors."

That worked out just fine during the introduction of Nehalem in 2008, he said. "DDR3 was ready to go when Nehalem was getting ready to ship, so that we weren't inhibited because of memory supplies and we were able to ship Nehalem parts."

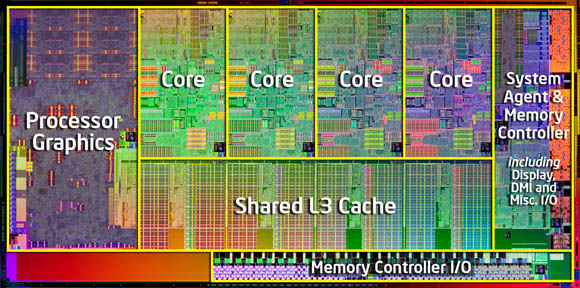

Among its many enhancements, Nehalem brought with it the QuickPath Interconnect (QPI) to replace the frontside bus, and an integrated on-die memory controller – another holdover from the Israeli P6-cum-Rambus work.

From Pawlowski's point of view, Nehalem was an architectural change equivalent in depth and breadth to the move from P5 to P6 – not surprising, considering that the Core architecture was an outgrowth of P6.

"Once Nehalem came along and just built on the Banias architecture and integrated the memory controller," he said, "it was a sweet part."

We asked Pawlowski which was more important to Nehalem's success: QPI or the integrated memory controller. "I'd like to say that it was QPI because I was running the group that designed it," he told us, "but it was the integrated memory controller. Getting the memory latencies down from the average of probably 180, 190 nanoseconds on a frontside bus down to 60 to 80 nanoseconds or 105 nanoseconds was huge."

Nehalem was a 45nm part, and a follow-on to the first 45nm parts – code-named Penryn – which introduced the second of Bohr's process improvements, high-k metal gate transistors. High-k metal gate arrived with the first Penryn chips, the Xeon and Core 2 processors, which appeared in late 2007.

"High-k" means having a high dielectric, or insulating capability. In the case of Intel's implementation, the high-k material is hafnium-based.

"We had to come back to the gate-oxide issue," Bohr told us, referring to the leakage caused by increasingly thin oxide layers. "We needed another improvement, and high-k metal gate was that improvement."

For Intel, he said, the high-k metal gate solution provided more than one benefit. "Number one, it allowed us to thin the electrical thickness of the gate oxide – it's physically thicker, but being a high-k material it has increased gate capacitance, which means it has improved transistor performance," he said.

"The other benefit is that we changed the gate electrode from polysilicon to a metal material," Bohr continued, "and that helped to improve transistor performance." The metal alloys used in these electrodes are different for the pMOS and nMOS devices, and remain Intel trade secrets.

"The third benefit," Bohr said, "is that we did the high-k metal gate transistors using a new process flow called 'gate last', where we first make the transistors using normal polysilicon gate electrodes, and so everything is kind of the same – patterning the gate electrode, forming the source drain. But then in the midsection of the flow, we strip out the sacrificial polysilicon gate electrode and then replace it with the high-k and the metal gate material."

Not only does this new manufacturing process make possible the construction of the high-k metal gate transistors, Bohr says, it also helps to enhance strain. "When you pull out the sacrificial gate electrodes," he said, "then the source-drain regions are free to push or squeeze the channel area, and you get more strain out of the channel and then more performance."

One process change, three benefits – not too shabby.

The next phase in Bohr's triumvirate of process-technology improvements – Intel's recently announced tri-gate or "3D" transistor structure – will first hit the streets when the company's 22nm "Ivy Bridge" chips ship next year.

But 2012 will be the beginning of the microprocessor's next 40 years, and this Tuesday we're hoisting a pint to the processor that kicked off the first 40: the Intel 4004.

But we're not going to stop with a nostalgic wallow in 40 years of Chipzillian ups and downs. Both Pawlowski and Bohr filled us in on a few things they see coming in the next forty years.

Of course, the predictions get a wee bit less solid as the future decades roll on, but The Reg will pass them on to you in a future article. But here's one teaser: how about a computing system that can harvest and reuse the energy used to power its transistors, rather than merely expending it?

"There's a lot of fun stuff going on," Pawlowski told us. We'll tell you about it soon.

Stay tuned. ®