This article is more than 1 year old

The life and times of Steven Paul Jobs

Empire-building inspirational visionary, or megalomaniacal swine?

Cancer, Intel, Pixar

On August 1, 2004, Jobs sent an email to Apple employees, saying that he had undergone an operation to remove a cancerous islet cell neuroendocrine tumor from his pancreas, that the operation had gone well, that he was taking a short break and would return to Apple in September – which he did.

When Jobs died on October 5, we detailed his recurring struggles with his health. We won't recapitulate them now. But we will pass on some of his own words, excerpted from his justly famous 2005 Stanford University commencement address:

About a year ago I was diagnosed with cancer. I had a scan at 7:30 in the morning, and it clearly showed a tumor on my pancreas. I didn't even know what a pancreas was. The doctors told me this was almost certainly a type of cancer that is incurable, and that I should expect to live no longer than three to six months. My doctor advised me to go home and get my affairs in order, which is doctor's code for prepare to die. It means to try to tell your kids everything you thought you'd have the next 10 years to tell them in just a few months. It means to make sure everything is buttoned up so that it will be as easy as possible for your family. It means to say your goodbyes.

Jobs at Stanford

I lived with that diagnosis all day. Later that evening I had a biopsy, where they stuck an endoscope down my throat, through my stomach and into my intestines, put a needle into my pancreas and got a few cells from the tumor. I was sedated, but my wife, who was there, told me that when they viewed the cells under a microscope the doctors started crying because it turned out to be a very rare form of pancreatic cancer that is curable with surgery. I had the surgery and I'm fine now.

This was the closest I've been to facing death, and I hope it's the closest I get for a few more decades. Having lived through it, I can now say this to you with a bit more certainty than when death was a useful but purely intellectual concept:

No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don't want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share. No one has ever escaped it. And that is as it should be, because Death is very likely the single best invention of Life. It is Life's change agent. It clears out the old to make way for the new. Right now the new is you, but someday not too long from now, you will gradually become the old and be cleared away. Sorry to be so dramatic, but it is quite true.

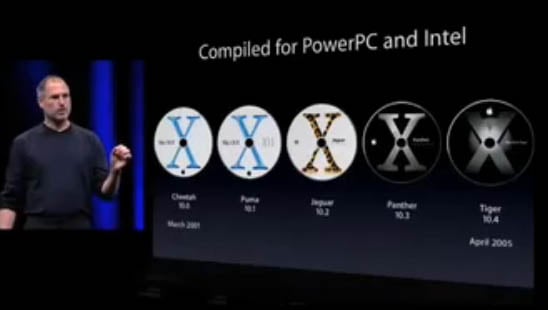

Jobs gave that talk on June 12, 2005. Just a few days earlier – June 6 – he had stood before a very different crowd: 3,800 developers at Apple annual Worldwide Developers Conference, where he confirmed the rumors that Apple was moving from the IBM/Motorola/Freescale PowerPC family of processors to the chips made by fervid fanbois' hated rival, Intel.

Jobs had chosen the right audience for this announcement. Although developers would bear the brunt of the transition because of the need to adapt their apps to the x86 architecture, they were savvy enough to know that this was a step that Apple had to make.

"I stood up here two years in front of you and I promised you this," Jobs told the devs, pointing to a slide with a photo of a Power Mac G5 and the text "3.0 GHz ?"

"And we haven't been able to deliver that to you yet," he continued. "I think a lot of you would like to have a G5 in your PowerBook, and we haven't been able to deliver that to you yet. But these aren't even the most important reasons."

The most important reasons, Jobs said, were that the future PowerPC roadmap didn't provide processors that would fit with Apple's plans for less-power-hungry platforms. Intel's chips were simply better than the PowerPC in terms of power consumption, and would increasingly be so in future generations.

Reactions to Jobs' decision were all over the map. Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer told Cnet: "There's more applications available for Windows than there are on Apple. All a chip change could do is probably slow that down because maybe there would be a big disruption with your ISV community ... What changes? I don't know."

One industry analyst castigated the switcheroo, telling PCWorld: "A wholesale move away from the IBM chips would be extremely foolish. Intel is not the 'de-facto leader in processor design' that it was a few years ago."

Another analyst credited Jobs with making a canny move – and one that was as much marketing as it was technical. "This takes some focus off of the PowerPC and the difference between Apple and everyone else – from a hardware perspective – and focuses more on the difference in the software," he told eWEEK.

"If you take away the hardware issues and turn it into more of an OS vs. OS type of situation," he reasoned, "this might be a good way [for Apple] to increase market share."

From The Reg's point of view, this last analyst was spot-on.

The first Intel-based Macs – the 15-inch MacBook Pro (replacing the PowerBook line) and 17-inch and 20-inch iMacs, all based on Intel's Core Duo processor – were announced at Macworld Expo on January 10, 2006.

The transition was completed at the next WWDC, on August 7, 2006, when the Xeon 5100–based Mac Pro and Xserve were announced, replacing the Power Mac G5 and Xserve G5, and handily beating the timetable that Jobs had announced at WWDC 2005, when he said that the transition would be complete "by the end of 2007".

At WWDC 2005, Jobs revealed that Mac OS X had always been compiled for both PowerPC and Intel processors

It's clear today that Jobs' decision to move to Intel was a wise one, but that was certainly not the case on June 6, 2005. Again – not to belabor the point – Jobs was right, and his detractors wrong.

During all this change at Apple, Jobs was still wearing another hat: CEO of Pixar, where he had his own set of problems to deal with. For example, there was that 1997 five-picture deal with Disney, which Jobs tried to renegotiate in 2003 with then–Disney CEO Michael Eisner.

It has been widely reported that Jobs' terms in that renegotiation were absurdly high, and designed to mightily tick off Eisner – the two men, simply put, loathed one another. In any case, after the renegotiation failed, Jobs said that any continuation of the Pixar-Disney partnership was a non-starter.

Jobs received some help in his anti-Eisner efforts from an unexpected source: Walt's nephew Roy, who sent a letter to Eisner, resigning from his seat on the Disney board of directors. Disney's letter, which was made public in accordance to SEC rules, detailing a series of Eisner's failings, and summing up: "In conclusion, Michael, it is my sincere belief that it is you who should by leaving and not me."

An ugly struggle for control of Disney ensued, including a rumor that Jobs would patch things up with Pixar if the Disney board fired Eisner. To make a long story short, Eisner was – eventually – stripped of his powers, he – eventually – tendered his resignation, and Disney president Robert Iger was – eventually – named CEO.

Iger's promotion came in October 2005. On January 24, 2006, Disney bought Pixar for $7.4bn, Pixar's creative soul John Lasseter became Disney's creative director, and Jobs became both a member of Disney's board and very, very rich.

Disney's Chicken Little: just fowl foul enough to make Steve Jobs a billionaire – again

One side note to this highly compressed review of the Disney-Pixar saga: rumors of the acquisition swirled for some time before the deal was announced, as is common in such mega-deals. One particularly entertaining one was that Disney was waiting to see how well its own computer-animated efforts, Chicken Little, would do at the box office, before it would pull the trigger on the Pixar deal.

The chicken earned a respectable $314m worldwide, but the Pixar-Disney films had uniformly done better: Toy Story had earned $362m; A Bug's Life, $363m; Toy Story 2, $485m; Monsters, Inc., $527m; Finding Nemo, $868m; and The Incredibles, $633m – and those numbers don't even include merchandising, Happy Meals, and the like.

By the way, the most recent Pixar-Disney film, Toy Story 3, has earned over a billion dollars in box-office receipts alone.