Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/09/16/ramac_55_year_anniversary/

Celebrating the 55th anniversary of the hard disk

The platters of Big Blue spawn that changed the world

Posted in Channel, 16th September 2011 14:00 GMT

All anniversaries are special, and so is this one. It's particularly special because a billion or more people have been and are being affected by it every day. They switch on their PCs and take advantage of Intel processors and Microsoft's Windows, or Mac OS, thinking nothing of it. But before these, and providing a foundation for them, came spinning disks, rotating hard disk drives, the electro-mechanical phenomenon that the world of computing has depended on for decades: 55 years to be precise.

Like much else in our pervasive IT world the disk drive's roots were laid down by IBM, and first appeared in a product called the 305 RAMAC, The Random Access Method of Accounting and Control, launched this week 55 years ago. Ah, those were the days.

IBM 305 RAMAC in use. The upright disk drive stacks can be seen inside the cabinets.

Cue drum roll

In the 1950s, magnetic drum storage was used with data stored in a recording medium wrapped around the outer surface of a drum. To get higher capacity the drum had to become bigger and bigger. It wasn't very space-efficient but you could have data continuously available instead of having to be read into dynamic memory from sequentially read-in, punched cards.

It's hard to imagine, but once upon a time there was no online data stored separately from a program's data in the computer's dynamic memory, which, of course, disappeared as soon as the application stopped running. The app couldn't be swapped out to disk to let another app in to memory. For one there was no disk and, for two, there were no multi-tasking operating systems.

Magnetic drum memory was a marvel but it was a bit like wrapping papyrus around a barrel; infinitely better than nothing, but not that great actually. What was needed was something with the same random access as drum memory but, somehow, more recording surface, much more, in the same volume.

Juking around

Suppose you could create a jukebox-like design: by stacking "phonograph records", only rather than grooved vinyl platters read with a steel needle, they would be the same recording media and read method as drum memory – only implemented as records, spinning platters, with concentric tracks of data.

There were engineering papers discussing the concept in the early 1950s but it was IBM, in a fantastic burst of innovation, that produced the first commercial hard disk drive product from its San Jose research lab facility in September, 1956. Univac could have got there first but stopped its own disk drive product so as to prevent the cannibalisation of its existing 18-inch drum memory product; a stumble which was followed by others as Univac became Sperry which became Unisys and has always, but always, been in IBM's shadow.

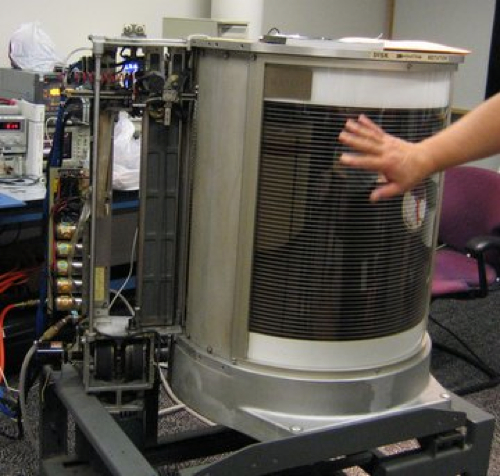

RAMAC disk stack.

Inside RAMAC there were two independent access arms which moved vertically up a stack of 50 disks, 24-inches in diameter, to the right disk, and then sideways across the target disk's surface to read and write data from the destination track. It took, we understand, 600ms to find a record in a RAMAC. The data capacity was 5MB (8-bit bytes, 7-bits for data plus a parity bit) and it would cost a business $38,400 a year to lease it. There was no popping out to your local Fry's to buy one...

The very first commercial RAMAC was used by Crown Zellerbach of San Francisco, a company dealing in paper, which is apt really – the idea of disk records replacing paper records.

Big Blue's spawn

IBM built and sold a thousand RAMACs, which probably bought the company around $30m – not bad at all. Big Blue stopped making it in 1961, five years after it was introduced, and replaced it with a better disk drive system: the 1405 Disk Storage Unit.

Hitachi GST hard disk drive, 500GB, 3.5-inch, spinning at 7,200rpm.

RAMAC gave birth to dozens and dozens of disk drive companies and formats but over time they were whittled down as manufacturing prowess and volume became as important as basic technology innovation.

IBM got out of the business, selling its disk drive operation to Hitachi GST, which is now being bought by Western Digital. Seagate is buying Samsung's drive operation, and Toshiba has bought Fujitsu's disk business. That's it, these are the disk drive survivors and millions of drives a year are pouring out of their factories.

Today's HDD is a compact and dense collection of technological miracles encased in metal box looking like any other slot-in piece of componentry. Inside are one, two, four or five platters with read/write heads on slider arms and a circuit board with chips on it. Each piece of equipment in there is fantastically highly engineered.

Big Blue's spawn is finally being threatened

Today we have 4 terabyte, 5-platter, 3.5-inch drives with a read/write head for each side of the platters. There is a 3 or 6Gbit/s interface to the host computer, and the drive spins at 7,200rpm with barely a sound. Faster drives that hold a few hundred gigabytes of data spin at 15,000rpm. The 305 RAMAC is a primitive beast indeed compared to today's Barracuda or Caviar drive. But dinosaurs were our ancestors, and RAMAC begat, eventually, Cheetah, Barracuda, Deskstar, Savvio, Caviar and every other disk drive brand you have come across.

Is the end in sight?

Until quite recently there has been no technology available to beat the hard disk drive combination of steadily increasing capacity, data transfer rate, space efficiency, cost and reliability. But the flash barbarians are at the gate with slightly better space efficiency, lower weight, much higher transfer rates, and also much higher cost.

Servers though need more data, much, much more data than before, and disk drives can't keep up. Big Blue's spawn is finally being threatened, and flash is taking over the primary data storage role with disk looking to be relegated to bulk data storage duties. We'll certainly still see disk in use in 10 years' time, but in 20 years' time and 30 years' time?

It's hard to say. However, the 55-year reign of this technology thus far has been an amazing feat and steadily increasing technology complexity combined with, and this is so amazing but taken so much for granted, steadily decreasing cost per megabyte of data stored. The whole HDD story is a testament to the effectiveness of high-volume manufacturing.

Over 160 million spinning disk drives will be delivered this year, with probably more next. They whir away inside our notebooks, PCs and servers, inside their anonymous metal cases, and serve up trillions of bytes of data over their lifetime. And we just take it for granted. That's the best tribute of all really. The technology inside these ordinary-looking metal boxes is so extraordinarily good that it just simply works, day after day after day...

Well, most of the time. Oh, what was that noise, that rending metallic sound? Oh, no, I've had a head crash. My data, oh good Lord, my data... ®