Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/03/03/hargreaves_and_google/

Google insists it couldn't have been British. Excuse me?

Some of my best friends are creators, says Hargreaves

Posted in Legal, 3rd March 2011 14:39 GMT

How curious. The Government's review into IP and growth may have been set up by mistake, or at least on a false premise. On announcing the review last November, Prime Minister David Cameron said something quite curious. Cameron explained that the review was a response to Google's concerns...

"The founders of Google have said they could never have started their company in Britain ... they feel our copyright system is not as friendly to this sort of innovation as it is in the United States," claimed Cameron.

So not surprisingly, the review has earned itself the nickname the "Google Review", and creative industries fear its recommendations will achieve Google policy goals at their expense.

It's certainly a very odd claim. Is copyright law really the insurmountable obstacle to the creation of search engines and content aggregators in the UK? The UK has, and has had, many such startups. Today, their biggest competitive disadvantage is not IP laws, but Google itself. Among potential investors, Google is the elephant in the room, and the biggest chilling factor for new investment. If you're lucky, very lucky, it may decide to buy you. Most likely, it will crush you. Set against this brutal reality, the IP review looks like a misdirection.

All of which leaves the review's head, Ian Hargreaves, in an unenviable position. Nobody wants to embarrass The Emperor. And judging by last night's performance at the Royal Society for the Arts, which was the only public outing before the review reports next month, Hargreaves will deliver exactly what The Emperor wants to hear. Hargreaves was invited, in various ways, to offer a glimpse into his calculations. But he declined. Any tally of economic winners and losers from various changes to IP law would be an unbalanced list. It's best not to make it at all.

The RSA panel brought Hargreaves himself together with representatives of publishing, music, the British Library ... and Google itself.

Sarah Hunter, the emissary from the Chocolate Factory, repeated the Cameron line.

"When Cameron launched the review, he said Google wouldn't have set up in the UK. It's true. Larry has said it publicly a number of times. Their view is that when you look at fair use it's relatively straightforward to assess if something is going to be legal. The law is not clear in the UK," said Hunter, Google's UK head of public policy. She suggested that if Google had been setting out in the UK, it would have changed its product.

"I don't believe IP is the problem," said Alison Wenham, representing independent music companies. "One of reasons Google did not start here is nothing to do with IP, it was to do with funding. The US has a rich culture of high risk investment and unfortunately our banking system does not value this, we have a criminal lack of funding for high risk ventures." She said she'd once taken her company's music catalog to be valued by the City, who gave it a valuation of zero. American investors valued it at $35m.

"There's no lack of business models, there's a lack of market traction, because we're all competing with free," she said. "What safe harbour and fair use has given US copyright owners is zero. Professor Hargreaves, you must be very careful what you wish for." Wenham wondered why Google promoted pirate sites so heavily, and why government agencies advertised the pirate sites.

The British Library's Dame Brindley had a list of five demands, which could be summed up as "give us an exemption for everything". The library wanted exemptions for music and visual works, for books, and wanted to restore the Digital Economy Act's Clause 43 for orphan works. None of these exemptions should be trumped by individual contracts. Simon Juden, head of public policy at Pearson, reminded the audience that fighting Google had cost the publishing industry some $30m in legal fees. He saw it as a technology problem, and proposed a global rights registry, something the music industry is building out in parts, for all content.

And Hargreaves?

Who gains and who loses?

"Politicians need to stand back rather than lean further forward," he said, perhaps wistfully.

He was asked in several ways whether he'd added up the economic gains and losses from such changes – and exactly who gains and loses. It's essential for Google to steer discussion well away from this, as job losses among the thousands of small businesses that depend on IP, and the tax receipts they bring into the Exchequer, are unlikely to be outweighed by any gains from Google or the Shoreditch startups which want such changes. Especially not tax receipts.

Hargreaves risked sounding sneery about "lone creators, heroic creators" – after being asked if he'd met any during the course of his meetings. "Some of my friends and some of my neighbours are such people," he said, sounding a little as if a family of noisy and smelly travellers had moved into his street. "I don't have trouble identifying with such people," he insisted. Yes, some of his best friends are creators. Really.

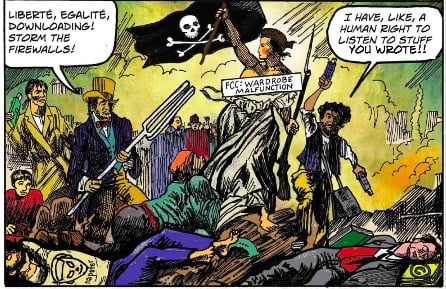

James Boyle's comic book Theft will be published next month. He is advising the IP review

Hargreaves concluded that he thought we were "only one-quarter of the way into the digital revolution", and repeated his view that creators weren't well served by the current copyright system, despite what they might think. When it comes to his conclusions next month, it isn't hard to guess who'll be happier with the outcome: the creative industries, or Google. Given the context in which it was born, the cynic would say there was never going to be any other outcome.

Oddly, trademarks and patents were not mentioned. ®