This article is more than 1 year old

Bigger than iTunes? Mobile operators lay out their app stall

WAC takes the warehouse approach

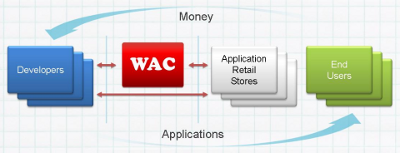

Operator consortium the Wireless Application Community has laid out its stall as an iTunes alternative, modelling itself as a clearing warehouse and leaving the retailing to network operators.

The WAC was announced in February, and since then has been busy assimilating the useful bits of the OMTP. It will now be swallowing the Joint Innovation Lab (JIL) to create a warehouse through which developers can distribute applications to network operators, and anyone else who fancies collecting the cash.

The WAC will be responsible for creating and maintaining a base level of JavaScript extensions to allow authenticated (AJAX) applications access to handset and network resources. Developers will then submit their applications to the WAC for approval and, once approved, the applications can be syndicated to network operators around the world for sale.

The developer sets the wholesale price of the application, and operators then add their preferred mark-up. The operator collects the money, through whatever billing mechanism they like, and the WAC then aggregates the cash and passes it back to the developer, taking a small cut to cover running costs.

The retail price of the application will be down to the operator, which might add the already established 30 per cent standard, but might choose to add more or less depending on local conditions.

If all this sounds familiar then it should: the Symbian Foundation is doing much the same thing with Symbian Horizon, though the WAC has aspirations on a much larger scale.

That scale will need supporting handsets, and the WAC is keen to emphasise that it's not just about smart phones, citing Samsung's Bada platform as an example of the kind of "lower-price" handset that will support the WAC platform. This is not a terribly good example though, given that the only Bada phone currently retails at more than £300.

The WAC is confident that by February next year it'll have demonstrable handsets and will be selling applications based on the JIL platform. Fully WAC-compliant devices will come in May 2011, based on the SDK, which will be available in November this year. But what really matters is how much those handsets will cost - it's easy to put something like the WAC onto an Android handset, but getting into feature phones will be more of a challenge.

Nevertheless the WAC's aims are reasonable given the limited scope of the planned APIs. Interesting stuff like in-application billing and location-based services won't come until later - the former not until operators support the GSMA's OneAPI which could leave WAC apps looking distinctly limited against their Android and iOS competitors.

But the WAC does have scale; with all the important operators signed up and a sensible business model it's possible to imagine mobile applications following ring tones into operator control. European operators missed ring tones completely, leaving third parties to rake in the cash as the market exploded. When operators did respond it was slow and clumsy, but their pure scale and presence steadily gained them market share. Today there are still third parties selling ring tones into a much-reduced market, but the operators are taking the lion's share.

It's easy to imagine the same thing happening with mobile applications, and that's certainly what the operators are hoping the WAC will deliver. ®