This article is more than 1 year old

So what we do when ID Cards 1.0 finally dies?

Jerry Fishenden argues the case for making next time non-evil

Why not blank? Or, why a card?

If you were designing a bank card today, it would have none of these flaws - it could even be blank if we wanted to take it to extremes. We could then decide what information we need to reveal, and to whom, by using our PIN to selectively disclose that information from a secure on-card chip when required. There would be nothing on the face of the card to copy or skim.

But talk of cards and identity cards is to miss the point. To lumber a modern identity policy with mandates about its delivery technology ("thou shalt have a card", enshrined in the very name of the 2006 Identity Cards Act) makes little sense. After all, why bother with cards at all? Although it may have escaped some policymakers' attention, we are living in a digital age. The majority of the population already carries or has access to technology that could be used as part of an effective identity strategy, mobile phones being an obvious example. Why not incorporate them into any national scale identity framework?

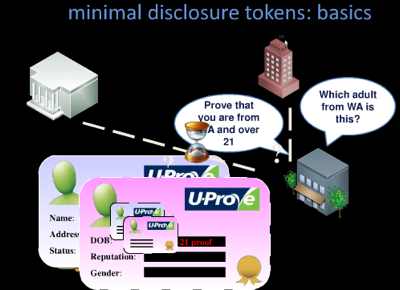

Stefan Brands' minimal disclosure tokens

In the work of leading identity, security and privacy thinkers such as Stefan Brands and Kim Cameron,* it is possible to see the art of the possible (Cameron's laws of identity can be found here). Stefan’s work on minimal disclosure, for example, makes it possible to prove information about ourselves ("I am over 18", "I am over 65", "I am a UK citizen", etc) without disclosing any personal information, such as our full name, place and date of birth, age or address. Neither would the technology leave an audit trail of where we have been and whom we have interacted with. It would leave our private lives private. Indeed, it would enable us to have better privacy in our private lives than we do today, when we are often forced to disclose personal information to a whole host of people and organisations.

The technology to build a secure, privacy-aware identity scheme certainly exists. But what remains largely absent at the moment is an understanding at the policymaking level of the art of the possible. This only goes to illustrate, once again, that technology is not being appropriately incorporated into the policymaking process both prior to and during the formulation of policy and the resulting Bills placed before Parliament. This is part of a wider failing that a future administration needs to fix unless it too wants to find itself reliving the recent history of major IT programmes beset with problems.

Planning for the death of the Act

With even the former Home Secretary David Blunkett apparently calling for the current UK product, identity 1.0 (the Identity Cards Act, 2006), to be withdrawn, we need an informed consultation on what a new identity 2.0 could look like. Well, for a starter I’d expect it to ensure:

- proof of entitlement and authorisation to access a service, without necessarily even identifying the user that is, the disclosure of only the bare minimum of information necessary for a transaction (for example, providing a proof that a person is over or under a certain age threshold, without disclosing their actual date of birth or their age)

- using a choice of devices that makes sense not only to government, but also to us as citizens and to the commercial sector

- the management of electronic credentials throughout the lifecycle between issuance and revocation, in a privacy-friendly way

- decentralised governance of identity infrastructure across the private and public sectors, without the need for anyone to sit in the middle and log and monitor everything we do

The technology exists to make this happen. But policymakers to date have lacked the technical understanding and vision to see the art of the possible and the agreed mechanism to deliver it. The good news is that there is still time for a reboot. Time for a twenty-first century identity framework that puts citizens in control, ensures there is a clear commercial value to the business community and sees government’s role limited to ensuring overall governance and compliance, providing an Identity Protection Service (IPS).

Now is a good time to be thinking about what such an identity framework might look like. If the current Act is repealed, we need an alternative, sensible set of ideas waiting in the wings. An alternative that is designed to strengthen our privacy and security, not undermine it. One that places us, as citizens, at the centre and in control – not at the centre under permanent and routine surveillance. And one that empowers us with additional safeguards and protections well beyond those that the current conman-friendly plastic cards in our wallets and purses provide.

The UK government can help raise the game for everyone here. So let’s hit Control-Alt-Delete on the current system and get that reboot started. I suspect it’s going to take a long time to reach agreement, so the sooner we start the better... ®

* Stefan Brands' U-Prove technology was bought by Microsoft last year. Kim Cameron is Microsoft's Chief Architect of Identity.

Until this month, Jerry Fishenden was National Technology Officer for Microsoft UK. He is currently a Visiting Senior Fellow at the London School of Economics.