Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2009/06/05/tob_minuteman_1/

Remembering the true* first portable computer

*The one that melts your face off

Posted in Bootnotes, 5th June 2009 18:42 GMT

A lot of folks tend to honor the Osborne 1 as the world's first mass-produced portable computer. The machine was admittedly an early pioneer in totable systems in 1981, but another, much-earlier computer perhaps really deserves the credit.

Some 20 years before the Osborne's release, the American government was already rocking a line of cutting-edge portable computers that — had they only been more widely released — would have melted any tech lover's heart. And their face. And probably most everything within a mile radius.

We're speaking, of course, of the first-ever guidance system baked into the US Minuteman 1 nuclear missile. Maximum portability: about 9,700 km (6,000 mi). Target demographic: Commies.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union successfully launched the world's first artificial satellite into orbit. Sputnik's celestial beeps gave voice to America's worst Cold War fears, but the true cause for concern was the rocket the machine rode in on. Sputnik's SS-6 rocket demonstrated that the Soviets had a launcher capable of hitting a target from thousands of miles away. A few years earlier, the government had detonated its first H-bomb. Add two and two together, and you get four horsemen of the apocalypse taking an American vacation.

Arise the threat of a US "missile gap." America promptly decided to dial its languishing ballistic missile program to eleven. They had called first dibs on the annihilation of humanity, after all.

You see, during this leg of the Cold War, the US was running under a doctrine of "massive retaliation" against a potential Soviet strike. Any attack on US soil meant all the chips were on the table.

But all-out nuclear war, as it happens, has a few major drawbacks — the aforementioned face melting for example, but that's only a concern for sissies. The real issue at hand was engineering.

Atomic explosions in the atmosphere can disrupt radio communications. Missiles at the time were controlled by ground-based computers, so huge amounts of radio interference made America's ability to direct a second volley of fission sandwiches unreasonably hard. And on the other side of such an exchange, not being able to control your rockets can make mutual assured destruction up to 50 per cent less mutual. What's the fun in that?

The solution developed was to put a digital guidance computer right dab on the missile. (Somewhere in the multiverse, Skynet cackles maliciously in anticipation). Easier said than done at the time, as a computer with dimensions less than that of a family sedan was considered slim and chic.

Just a Minuteman

On February 27, 1958, the Air Force secured approval to develop the Minuteman program. The goal was mass-production of efficient, highly-survivable intercontinental ballistic nuclear misses that could sit unattended for a span of years.

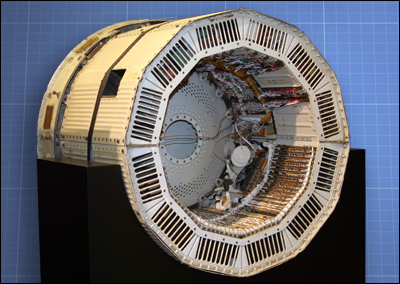

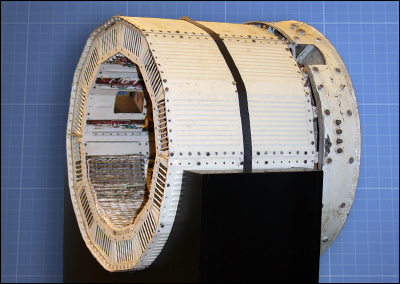

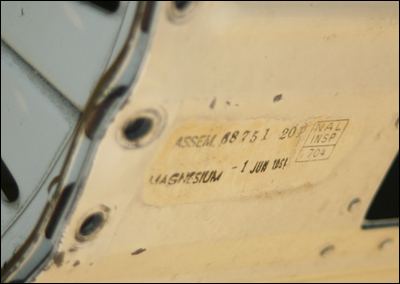

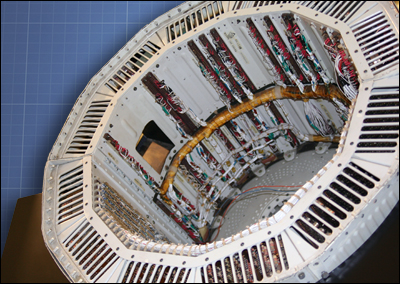

The Minuteman 1's missile guidance computer was a bleeding-edge 24-bit microcomputer made by Autonetics Division of North American Aviation. The 62-pound, fully solid-state computer contains 6282 diodes, 1521 transistors, 1116 capacitors, and 504 resistors mounted on 75 circuit boards. Memory is a 5,454 words (2,727 double precision) and its speed tops out at 12,800 additions per seconds.

The guidance system was the most advanced for a ICBM at its time. Targeting was done by software running on a mainframe computer, but flight control was fully automated once the missile left its silo. Once it was launched, the guidance system couldn't be changed from the ground. The computer was also assigned the double duty of running diagnostic checks while it waited.

That way, the missile could go unattended for years before teaching the world that Providence abhors an economic system in which wealth, and the means of obtaining wealth, are not privately owned. Although the computer's capacity for a second job added extra weight, this was more than offset by the cabling which would have been required for external diagnostics.

Minuteman's brain was was fit into a cylindrical package above the rocket's third stage. A segment up was the missile's penetration aids, and above that, the all-important nuclear warhead. The on-board system navigated by measuring velocity with gyroscopes and acceleration with an accelerometer - sort of like a Nintendo Wii controller, only slightly more deadly when you accidentally toss it at your television set.

In short, the Minuteman I's computer offered thousands of miles of portable computing before folks could even dream of lugging around the Osborne 1 on holiday.

A big hit (metaphorically)

After a successful initial test flight in 1961, the US Department of Defense formally green lighted the Minuteman program. The missiles turned out to be a big hit, although thankfully never literally.

But it's important to note the system represents more than Cold War posturing. The computers we use today owe quite a deal to the Minuteman program.

Advances in technology combined with president John F. Kennedy's switch to a "flexible response" regime to a potential Soviet strike drove home the need for a new generation of Minuteman missiles. A new requirement of being able to re-target and reprogram a missile moments before launch was something the Minuteman I's discrete circuitry simply wasn't up to. Because of that, Autonetics turned to integrated circuits for the Minuteman II's navigational computer. This change in tech nurtured IC production in its infancy through the early 1960s from pioneering companies like Westinghouse, Texas Instruments, and RCA.

Minuteman II's navigation system was nearly one quarter the size of Minuteman I with approximately two and a half times as much memory. Midway through the decade, the Minuteman project was responsible for about 20 per cent of all IC sales and had become the largest purchaser of semiconductor microcircuits. While the American government's direct contribution of integrated circuit R&D is arguably modest, it was undeniably the technology's sugar-daddy.

We should celebrate this wonderful nuke. Oh sure, the computer system couldn't run "Wordstar" or a game of "Colossal Cave," like the Osborne 1, but how many computers do you know that can destroy the world? That feature offers some serious LAN-party cred right right there. And with a three-stage, solid-propellant rocket build in, travel is a breeze.

As always, our thanks to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California for letting us drool over their machinery. For those interested in finding more Minuteman 1 history and data, check here and here for a megaton. ®