This article is more than 1 year old

Scientists discover galaxy's youngest supernova

Victorian stellar explosion

Where have all the Milky Way's supernovas gone?

Contrary to what would seem a basic survival instinct, many astronomers are positively keen to get more catastrophic, solar-system-busting explosions in our home galaxy. But until recently, a good Jerry Bruckheimer space opera hasn't appeared to reach Earth since the seventeenth century.

Researchers announced today they discovered a supernova in the Milky Way that would have begun as early as the late 19th century from the Earth's perspective.

The remains of the star - dubbed G1.9+0.3 - is not only the youngest known supernova in the galaxy but also helps fill a puzzling lack of stellar destruction seen in our corner of the universe.

The supernova remains are estimated to be about 28,000 light years away, near the center of the Milky Way. Observations by the Very Large Array (VLA) radio observatory in New Mexico and NASA's Chandra X-ray observatory only recently identified the explosion as the most recent known solar death in our galaxy.

The previous record holder for youngest galactic supernova was Cassiopeia A, that exploded from Earth perspective in 1680. But scientists believed there should be way more.

Often times finding supernovas in our own galaxy is considerably more difficult than it is for foreign ones. Clouds of gas and dust that comprise the Milky Way — getting denser near the center — obscure stellar explosions from being spotted at our plane of view inside of the same galaxy.

Stupid space dust blocking our view...

But astronomers regularly see supernovas in galaxies similar to our own. Based on those observed rates, they estimate the Milky Way should host exploding stars about two or three times each century.

"If the supernova rate estimates are correct, there should be the remnants of about 10 supernova explosions that are younger than Cassiopeia A," said David Green of the University of Cambridge, who led the VLA study. "It's great to finally track one of them down."

When G1.9+0.3 supernova light reached Earth about 140 years ago, astronomers at the time would not have been able to observe the shock waves through optical means. Embedded in the dense field of gas and dust in the center of our spiral galaxy, the supernova is made about a trillion times fainter that it would have been from Earth with a clear line of sight.

The supernova remnants suggest that a lack of similar sightings in the Milky Way is largely due to obscuration. But the researchers can't yet rule out the idea that our galaxy is simply different in its supernova activity or that younger supernova remnants look different than previously imagined. Further observations of the newly discovered star remains are obviously of some interest to the researchers.

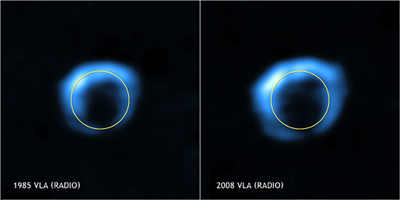

G1.9+0.3 was first spotted in 1985 when astronomers lead by Green identified the remnants through radio signal. However, because of its relatively small size, it was originally believed to have resulted from a supernova that exploded about 400 to 1,000 years ago.

Twenty-two years later, when Chandra observed the remnants, they saw it had expanded by a surprising amount — about 16 per cent since 1985.

In recent weeks, VLA began tracking the object again to get an "apples to apples" comparison of the remnant's expansion. By comparing the supernova remnants expansion, they now figure the supernova could have happened by our time as early as the late 1800s.

Given the immense distance the explosion was from Earth, from the star's own perspective it exploded about 28,000 years ago — or yes, 28,140 years if you're a stickler for detail. But the limits of light speed allow us a chance to observe the explosion as if it was 140 years after the star kicked the bucket.

"No other object in the Galaxy has properties like this," said Stephen Reynolds of North Carolina State University, lead of the Chandra study. "Finding G1.9+0.3 is extremely important for learning more about how some stars explode and what happens in the aftermath." ®

Bootnote

An interesting thing about covering astronomy is that it's a subject where the full moon is always out, so to speak.

NASA apparently isn't too choosy about who it lets into its news announcement conference calls or who it lets ask questions to the scientists involved.

Two queries into the Q&A segment, a man began asking questions that veiled rather obscure racial slurs. The "terminology" baffled the scientists and moderator alike, who asked him to repeat himself a few times. (We later had to look up the terms he was using to identify that he was, in fact, being racist rather than just plain crazy.)

Again, as the moderator began wrapping up the call, her voice was buried under someone mashing telephone buttons (odd, because listeners were supposed to be on mute). Then a caller shouted, "HEY! I WANT TO TALK TO YOU GUYS! LET'S TALK ABOUT YOU GUYS PLAYING WITH YOUR VAGINA!"

At that point, the moderator bailed out of the call, leaving the scientists wondering if it was over. After some ponderous discussion, Green observed:

"Except for a couple of loonies, I think that went well."

The conference call is supposed to later be repeated on a loop at NASAs website. Should be interesting to see how it all gets edited out. ®

Bootnote 2: return of the bootnote

Thank you readers who pointed out our time disparity issues.