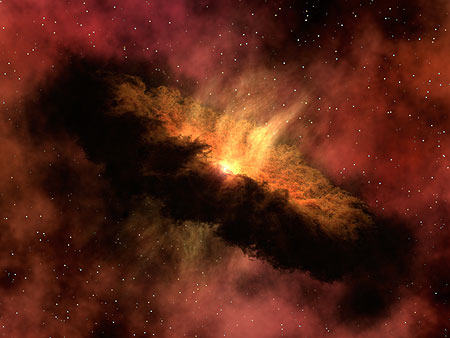

Somewhere in the universe, a solar system is forming. Whirling around the newly ignited stellar embryo is a disk of dust, gas, and rocks that will gradually settle down into a stable planetary system. And according to astronomers using the Spitzer space telescope, the natal cloud - the region where planets will form - is being deluged with water vapour.

The scientists say new data from the telescope shows that enough water to fill Earth's oceans five times over is falling into the planet forming region around the star system NGC 1333-IRAS 4B, and smacking into the dust and rocks that will gradually collect together to form comets, asteroids and even planets.

"For the first time, we are seeing water being delivered to the region where planets will most likely form," said Dan Watson of the University of Rochester, New York.

"On Earth, water arrived in the form of icy asteroids and comets. Water also exists mostly as ice in the dense clouds that form stars. Now we've seen that water, falling as ice from a young star system's envelope to its disk, actually vaporises on arrival. This water vapour will later freeze again into asteroids and comets."

Watson explains that because water is easier to detect than many other molecules, it is a useful indicator for astronomers seeking to learn more about the physics and chemistry of the disks around newly formed stars.

The team has discovered that the disk in NGC 1333-IRAS 4B stretches out beyond the radius of Pluto's orbit around our sun. It is relatively dense, with 10 billion hydrogen molecules per cubic centimetre. Although these facts provide relatively little clue to the star system's eventual size, they will help astronomers understand more about how planets form.

"We have captured a unique phase of a young star's evolution, when the stuff of life is moving dynamically into an environment where planets could form," said Michael Werner, project scientist for the Spitzer mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Finding the system is a stroke of luck, too. The observing team targeted 30 known stellar embryos, but only NGC 1333-IRAS 4B tested positive for water. This wet phase of a star's evolution - where ice from the stellar envelope falls towards the star, vaporising as it hits the disk - is short-lived, and hard to catch.

The star-system, located 1,000 light-years away in the constellation Perseus, also happens to be at just the right angle for us to view the stellar core, the team says.

More details, and pictures are here. ®