This article is more than 1 year old

Sun's chip gurus theorize about obliterating IBM and Intel

Nearing proximity

When you have companies such as IBM and Intel looking to destroy your business, it's nice to have a fella like Ivan Sutherland stored away in a back room.

Sutherland, considered the father of computer graphics, developed a method of linking processors together called face-to-face computing, as part of his work at Sun Microsystems Labs. Over the years, Sun has changed the name of Sutherland's technology to “proximity communication” and has inched closer to rolling it out in actual product. Should the proximity communication bet pay off as expected, Sun could enjoy a massive performance boost over rivals in the server game and possibly in areas such as networking as well.

Sun claims to be doing nothing short of rewriting Moore's Law with the proximity communication technology.

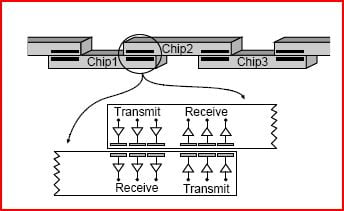

The main concept behind proximity communication proves easy enough to grasp, as you can see from the diagram. You have downward facing chips that sit on top of upward facing chips, allowing the two sets of chips to make a direct, electrical connection. This removes the need for wires between chips and awkward multi-chip modules employed today by some vendors.

We turn to one of Ivan Sutherland's face-to-face patents to explain some of the drawbacks associated with wiring chips in today's configurations.

This elaborate arrangement of connectors from one chip to another has two drawbacks. First, it is costly. There are many parts involved and many assembly steps to put them together. The steps include making the packages, installing the integrated circuit chips in them, bonding the pads of the integrated circuit to the conductors in the package, and fastening the packages to the printed circuit board. Although each of these steps is highly automated, nevertheless they remain a major cost factor in many system designs.

Chip Fornication

Second, it is electrically undesirable. The wires on the printed circuit board are about 1000 times as large as the wires on the integrated circuit. Therefore, to send a signal from one integrated circuit to another requires a large amplifier on the sending integrated circuit. Moreover, the conductors involved have a good deal of electrical capacitance and electrical inductance, both of which limit the speed at which communication can take place. Perhaps worst of all, much energy is required to send a signal through such large conductors, which causes the driving integrated circuit to dissipate considerable power. The cooling mechanisms required to get rid of the resulting heat add cost and complexity to the system.

Several methods have evolved to improve chip to chip interconnect. One way is to avoid several packages for the separate integrated circuits. Instead of a package for each circuit, several chips are mounted in a "multi-chip module," a kind of communal package for the chips. The multi-chip module (MCM) contains wiring that carries some of the chip-to-chip communication circuits. The size of the wires in the MCM is smaller than the wires on a printed circuit, but not yet so small as the wiring on the chips themselves. Electrical capacitance and inductance in the wires between chips remains a problem even in MCMs.

To pull off Sun's proximity communications arrangement, the company must find a way to align the chips for capacitive coupling with 15 microns of accuracy for top performance. Thus far, that has proved pretty tough, although Sun is making strides in the right direction.