If you were trying to work out how long a day on Saturn is, you wouldn't expect to find your best efforts scuppered by a tiny moon. After all, you can still see the planet, right?

The problem lies in the technique traditionally used to discover how fast a gas giant is rotating. The radio technique measures the rotation of the planet by taking its radio pulse rate - the rhythm of natural radio signals from the planet. If something is slowing the planet's magnetic field, this won't work.

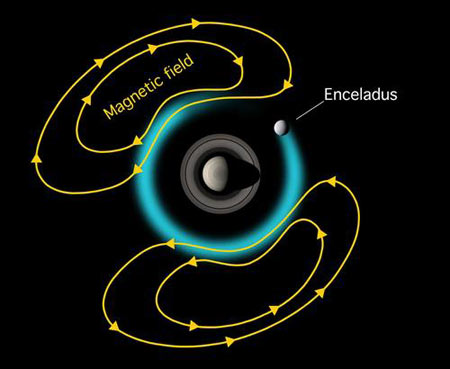

But this is exactly the problem facing scientists right now: the moon Enceladus is weighing down the gas giant's magnetic field to such an extent that the planet's field is being slowed down. This makes the radio technique as useful as a chocolate fireguard.

"No one could have predicted that the little moon Enceladus would have such an influence on the radio technique that has been used for years to determine the length of the Saturn day," said Dr Don Gurnett of the University of Iowa, principal investigator on the radio and plasma wave science experiment on NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

According to new research, published in the 22 March online issue of Science, the cause of the drag is Enceladus' polar geyser: a vast stream of ice and water vapour emanating from the moon's southern pole. These particles become electrically charged and are captured by the planet's magnetic field, forcing the field lines to slip relative to the planet's actual rotation.

The findings are prompting scientists to question the absolute link between a planet's radio pulse rate and the length of its day.

Professor Michele Dougherty, principal investigator on Cassini's magnetometer instrument from Imperial College London, says: "Saturn is showing we need to think further."

The findings explain an earlier observation that the apparent length of Saturn's day as measured by Cassini is now about six minutes longer than when it was measured by Voyager in the 1970s.

The researchers now have two possible explanations for the apparent slowing of Saturn's rotation: either the geysers are more active than they were in the 1970s, producing more material and thus slowing the field line's rotation; or there are seasonal variations according to where Saturn is in its 29 year orbit of the sun. ®

Bootnote: NASA has audio clip files to go with this. Point your ears this way and listen in on Saturn.